Dec. 5, 2018

50 years after founding, VCU works to fulfill its vision

Share this story

Charles McLeod did not come to Richmond Professional Institute to be a pioneer. He came to play basketball.

“I thought I was going to set the world on fire. I knew I was going to the NBA. I just thought I'd go to college for a couple of years to hone my skills,” McLeod said. “Funny thing happened on the way to the NBA: I realized I wasn't nearly as good as the kids who signed my high school yearbook said I was.”

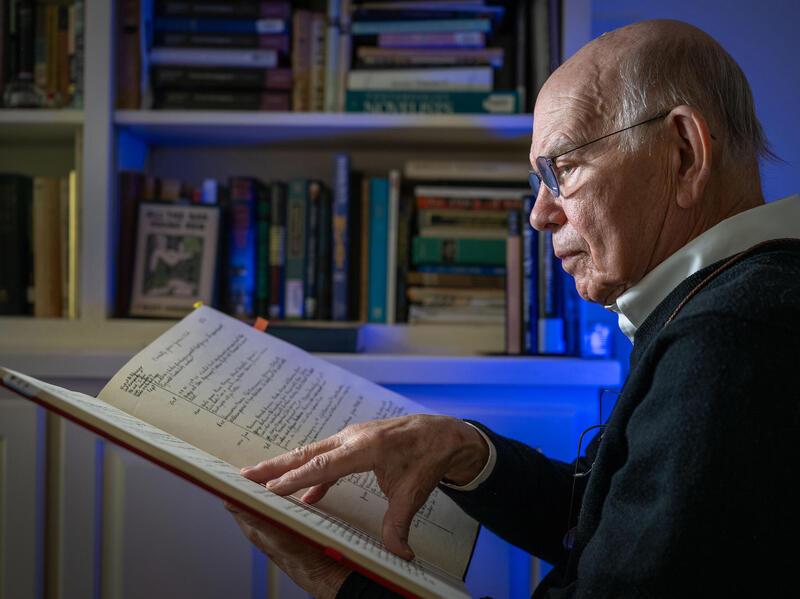

McLeod, Ed.D, now an educational consultant and motivational speaker, enrolled at RPI in 1966, two years before it merged with the Medical College of Virginia to form Virginia Commonwealth University. He did play college basketball, becoming the first African-American player at RPI. But he was also known during his undergraduate days as a co-founder of VCU’s first African-American student organization and a member of a small group of students who challenged the new university to embrace its identity as an urban institution.

The group advocated for the creation of an African-American studies department and an increased emphasis on recruiting more black students and faculty.

“Our frustrations and the frustrations of African-American students was the fact that VCU really didn't reflect the community at all,” McLeod said, reflecting on the years immediately following the MCV-RPI merger. “[We were] six young black men who were just determined to make this place different. We read the Wayne Commission [Report] and we were intrigued by it, but more importantly we wanted to make sure this university became a truly urban university, not just in address but in attitude, that it really projected the needs of the urban community.”

Connecting the city’s colleges

VCU was born during a time of change and turmoil, McLeod and others recalled Nov. 30 at a symposium marking the 50th anniversary of the university.

“Richmond in 1968 was not unlike today in many ways,” said Bill Martin, director of the Valentine museum. “There was a real sense in the nation, in the commonwealth, in the city, that things are coming apart. But also that change was in the air.”

A new city hall, a downtown arena and an expressway were under construction. And national turmoil was causing unrest, Martin said.

“We see the assassination of Martin Luther King and riots on Broad Street, the assassination of Robert Kennedy, the unraveling of Vietnam with the Tet Offensive. There are anti-war protests in Monroe Park,” Martin said. “And it’s within this context that VCU becomes a place.”

The Wayne Commission set the framework to connect the city’s two colleges. The merger was a massive undertaking, said John Kneebone, Ph.D., associate professor in the VCU Department of History. It also was not without its detractors. However, it became the most important moment in VCU’s history, said Eugene Trani, Ph.D., who served as VCU president from 1990-2009.

“That is the most important thing,” Trani said. “It was [about] integrating [disciplines], research efforts on both campuses, creating the VCU Health System. We are now a university and recognized as a university and that was the most significant thing the Wayne Commission hoped for, and I think that promise has been fulfilled.”

Unsung heroes and pivotal moments

Along the way, Martin said, were pivot points, growing pains and the emergence of influential people who helped steer VCU in the five decades following the merger.

Kinloch Nelson, M.D., who served as dean of the MCV School of Medicine from 1963-71, was one those people, said Jodi Koste, archivist and head of special collections and archives at the Tompkins-McCaw Library.

“He was the dean of medicine at a pivotal time,” Koste said. “He got faculty to finally agree to the new modern medical curriculum in 1964. He also helped smooth the way with the merger. He very much tried to put out some of the fires and encouraged people to give the new university an opportunity.”

So, too, did David Hume, M.D., a transplant specialist who came to MCV from Harvard University. Hume is best known for performing the first kidney transplant in Virginia in 1957, but he also helped quell a group of influential MCV alumni who wanted to unravel the merger, Trani said.

“[They] were trying to recreate the Medical College of Virginia as a separate institution,” Trani said. “And Hume really went after them and said they needed to support the university and spend their time with the legislature to give the university and its medical center as much flexibility as it can have in terms of clinical operations.”

The names of those who helped advance the university in similar fashion are too many to count, Kneebone said.

“If I start naming names I’ll end up leaving out important people,” he said. “I do a lot of oral history interviews and the striking thing is that everyone I spoke with — administrators, faculty, former students — everyone is proud of the part they had in making this university.”

Other key moments are more widely known, including the creation of the Virginia Biotechnology Park early in Trani’s tenure, the early 1990s partnership with Virginia Tech that formed what is today the VCU College of Engineering, the establishment of an arts campus in Doha, Qatar, and VCU’s 2011 run to the Final Four in men’s basketball.

Each, Kneebone said, strengthened VCU and the city.

“VCU has been an anchor for the city of Richmond, and Richmond is on the way up as VCU is,” Kneebone said. “They have done so together.”

‘A different kind of place’

Speakers at the symposium said they see a university today that is growing — and also still grappling with key issues related to its urban identity, including moving beyond the idea of “cosmetic diversity” to create a truly inclusive environment, said Chaz Barracks, a doctoral candidate in VCU’s Media, Art and Text program.

“When I was an undergraduate student at University of Richmond, I would walk through this campus quite a bit and I felt that VCU was so diverse. I would see black people and I would see arts students and women and students I wasn't seeing at University of Richmond as much,” Barracks said. “But when I got here, you know, diversity is typically on the bottom; it's never represented as much at the top. So when I sat in my first Ph.D. class as a first-generation college student, I’m one of two black men in our whole program.”

Efforts to elevate equity at VCU are numerous, including grants to increase female faculty recruitment and advancement in STEM fields, projects to help more black men get into medical school, and expanded research in LGBTQ studies. Today, 33 percent of first-year VCU students are the first in their family to attend college. The university also is engaged in conversations regarding Confederate symbols that exist on its campuses and the ways history is, and will be, commemorated at the university.

“I see a university [today] constantly struggling to make itself relevant to the community,” McLeod said. “Haven’t gotten there yet, but at least the institution is honest about its imperfections and is willing to work on those things.

“We saw the potential for this place and we saw us being at the ground level,” McLeod said of his efforts in 1968. “This was supposed to be a different kind of place, not the traditional Southern, predominantly white, liberal arts college with rolling hills, palatial quads. This was hard, in the city. We said to VCU, ‘You wanna to be urban, you gotta be urban. Be what you say you are.’”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.