Nov. 19, 2019

Enrique Gerszten has been inspiring physicians-in-training for six decades

Share this story

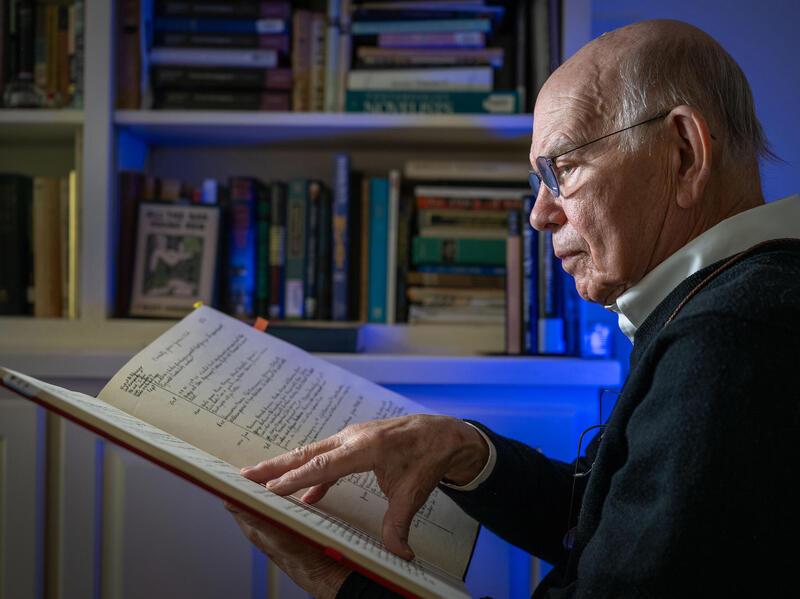

Enrique Gerszten, M.D., delights in the chance encounters that often enliven his days. Typically, they start with someone surreptitiously watching him, studying his face as though wanting to make sure they recognize the man they think they see. He can be anywhere when it happens. Recently, he’d just gotten onto a crowded elevator when a woman seemed to be stealing glances his way. Sure enough, she introduced herself and told him, “Dr. Gerszten, I took your class years ago.”

Gerszten, a professor emeritus of pathology in the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, has taught more than 10,000 students, residents and fellows during his 59-year tenure, and he’s proud of the way his lessons seem to stick with these students long after they’ve left the classroom. When a former student recognizes him and makes a point of introducing themselves, Gerszten is eager to learn about their careers and experiences. Often, they tell him something they have always remembered from his class, perhaps the enduring appeal of his distinctive Argentinian accent or the preserved specimens he has long used to show the unique ravages of diseases that have since been eradicated or made much less common. Gerszten has been teaching so long that sometimes these former students have completed their entire careers and gone into retirement.

Of these serendipitous meetings, Gerszten says, “I love. I love.”

“I’m very happy that they recognize me, though I cannot recognize all of them — there are so many of them,” he says. “They tell me stories about what they learned, what they remember, and it makes me very happy.”

An Argentinian upbringing

Gerszten was born in 1927 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. As a child, he lived near the city’s zoo and his earliest recollection is of throwing a stone toward a tiger that lived there. The animal tried to swallow the stone, grew fiercely agitated, and Gerszten fled the scene in fear. His second memory is of playing soccer in the street when the Graf Zeppelin flew over Buenos Aires. The city’s children, including Gerszten, screamed afterward, “I saw it! I saw it!” However, Gerszten had not actually seen it, as he’d been too interested in his soccer game and never looked up to catch a glimpse of the marvel.

When he was 15, Gerszten began to work in an office, taking high school classes from 8 p.m. to midnight. He would walk the 10 blocks home from school alone at night accompanied only by the city’s population of wandering cats. When he reached home, he would position himself under a streetlight and study into the early morning hours rather than risk disturbing his family.

Despite his love of soccer, he came to realize that he lacked the natural talent to go far with the sport and should focus on his academics, though he did play a few games in a lower division of the prominent Argentinos Juniors club. After high school, he attended the University of Buenos Aires School of Economic Sciences and worked in a government office that was a combination of a bank and a credit union. His studies were interrupted by a year of compulsory service in the army, but he returned to school and earned the country’s highest degree in accounting. Shortly after graduation, at age 23, he was made chief of accounting in his office and handed oversight of more than 40 employees.

Still, Gerszten was dissatisfied with the work, which felt routine and insufficiently challenging. Because he had the highest degree his university offered, he was free to enroll without any prerequisites at another of the country’s universities. He decided to start studying medicine — a pursuit he’d long been considering — while keeping his full-time job. His friends and family thought he was crazy. In fact, he says his girlfriend gave him “a pink slip” the day after he told her.

But he loved medicine and after a rocky start thrived academically. He wonders if he would find the same level of success as a student today with so many available distractions — TVs, computers, cellphones. “If I had all of that, I don’t know that I would study enough,” he says.

Gerszten finished his degree at 30, resigned from his job and served a yearlong internship at a free clinic in an impoverished neighborhood, where he treated patients without pay. He occasionally received presents from grateful patients, including a knitted vest that he still wears on special occasions.

He learned from a fellow physician about residency programs in the United States for graduates of foreign medical schools. In June 1959, he left Argentina on a propeller plane for New York, where relatives awaited him. In New York, he started a pathology residency at Goldwater Memorial Hospital.

A career in the U.S.

In 1960, Gerszten transferred to the Medical College of Virginia to finish his residency, moving with his new wife, Ellen. After completing his residency, he stayed on, starting his academic career as an instructor in 1963. From the outset, he was devoted to all aspects of his work — service, teaching and research. He specialized in autopsies. His first research publication, which was on the effects of antibiotics on tuberculosis, appeared in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association. The article was later recognized as one of the most important publications on the subject and appeared in The Yearbook of Drug Therapy. He still has a copy of the book in his Sanger Hall office.

That early success strengthened Gerszten’s confidence.

“It helped with my desire to continue practicing in an environment of academia,” Gerszten says.

He remembers with fondness that period of intense, demanding work, memorialized in part in his office with a photograph of the hospital from those days. His teaching responsibilities grew over the years as MCV became VCU. Starting in 1976, he taught a pathogenesis course that had a crucial influence on the many students who took it, and he was a strong advocate of the School of Medicine’s adoption of an integrated curriculum. He also served for decades on the admissions committee of the medical school, interviewing student applicants, as well as on a number of other committees.

In addition, Gerszten developed teaching and research tied to paleopathology, the branch of science focused on the pathological conditions found in ancient human and animal remains. In particular, Gerszten has done extensive research into South American mummies, including conducting autopsies on hundreds of bodies, and has earned national and international recognition for his groundbreaking work in the field.

An energetic, hungry mind

Gerszten’s career at VCU has always been marked by an authentic, wide-ranging curiosity. Ann Fulcher, M.D., chair of the Department of Radiology at VCU, took Gerszten’s class when she was a student and now counts him as a colleague. She enjoys the impromptu conversations, often on medical topics, she has had over the years with Gerszten in the Sanger Hall hallways, and also collaborates closely with him on his mummy research. She says these days she often sees him in the parking deck early in the morning, dressed in his lab coat or a jacket and tie.

“He looks ready for business every day I see him,” she says.

Fulcher says Gerszten has an insatiable enthusiasm for the field of medicine — “he’s always interested in what I’m doing in radiology,” she says — that is infectious for his colleagues and students.

“I think he’s one of the most engaged and energetic individuals in our entire institution,” Fulcher says. “He’s always ready for a challenge. He’s always ready for a new project. He’s always motivated. He’s kind of got that twinkle in his eye all the time, and I think that really encourages everyone around him.”

Gerszten says he never pushed his two sons toward medicine or even discussed the profession in detail with them, but he believes his evident love and devotion for his work may have influenced them as they considered careers. Both followed in his footsteps. Robert is a professor of medicine at Harvard University, while Peter is a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Pittsburgh.

Gerszten says the intellectual challenges of pathology have been a good fit for him. He appreciates the role he plays helping patients without ever meeting them.

“I don’t talk to patients, but I do talk to a microscope on behalf of them,” he says.

With Gerszten’s decades of experience, rare is the case that stumps him. In fact, when he works with residents on an autopsy, he sometimes tells them that he can diagnose a particular case without using a microscope, considering factors that he can access without that tool of the trade.

“I tell them what it is and I know they are skeptical of what I’ve said but later the microscope confirms it,” Gerszten says.

A beloved teacher

Gerszten merges his love of pathology and medical history in the class that he still teaches to fourth-year medical students called Paleopathology and the History of Medicine. He says he believes it is essential for physicians to understand medical history and the broader context of their work. Michelle Whitehurst-Cook, M.D., associate professor of family medicine and population health and senior associate dean of admissions for the School of Medicine, says the value of the course is evident.

“Medical school is full already with what students have to know for their boards, and this offers something that they may not need for that but that provides great lessons for moving ahead in a life in medicine,” says Whitehurst-Cook, one of Gerszten’s former students. “It pulls together everything they’ve already studied and gives them new knowledge they wouldn’t have otherwise gotten. And it will help them deal with some of the problems and issues that physicians must deal with every day.”

Among the highlights of the class is when Gerszten shares examples from the pathology department’s “museum of specimens,” which show the effects of various diseases that have largely been eliminated, such as smallpox or diphtheria, and that the students likely will never encounter in their practices. The students inevitably are fascinated.

“They love it,” Gerszten says. “They write me letters and always mention that about my course.”

Gerszten is constantly coming across letters, notes and photos from students in his office at VCU and at home. Just like the chance meetings in public, these discoveries give him a thrill. He might be sorting through a drawer and come upon a note and photo from a student he taught 20 years ago, as he did recently, and then he will see if he can locate them online so he can give them a call. Right now perched in his office is a large framed photo of a recent crop of VCU medical students who traveled to Argentina after they received the matches for their medical residencies. The photo, which includes written thank you notes to Gerszten from each student, was taken in front of the Andes at a spot he had recommended they visit.

“The bond between a teacher and a student can be forever,” he says.

Whitehurst-Cook says Gerszten’s teaching leaves an impression on students for a host of reasons, including his accent (“Everyone loves it,” she says), his sense of humor, the clarity of his lessons, the depth and breadth of his knowledge, his compassion for his students, and his ability to emphasize the most important points, rather than hiding them in the weeds. Gerszten’s skill and enthusiasm for teaching led to the School of Medicine renaming its highest teaching honor for him in 2008. The Enrique Gerszten, M.D., Faculty Teaching Excellence Award is presented each year to a faculty member for outstanding teaching achievements.

“He really does love his students and he loves teaching,” Whitehurst-Cook says. “He loves mentoring and he’s mentored quite a few of us to be better teachers and educators. He’s an excellent motivator of people. He motivates you to want to be a good student so that you can eventually be a good clinician. He builds an excitement in learning, and I think that is the most important characteristic of an excellent teacher.”

Emeritus

Gerszten still reports to his office three days a week, arriving at 7 a.m. and leaving around 3 p.m. When he started at MCV, he routinely worked seven days a week, but he acknowledges that his more modest workdays now feel long in comparison. However, his mind is as restless and indefatigable as ever, and he still makes a habit of following the whims of his bottomless inquisitiveness into intense study of intricate subjects and deep discussions with colleagues. He reads medical journals and remains as captivated by the newest findings as he ever was. He also continues to co-chair the program of the Paleopathology Club that he co-founded and that meets each year at the U.S. and Canadian Academy of Pathology meeting.

Gerszten says he spends a lot of time now thinking about his past and the world’s future. He thinks about Argentina — his life there as a youth and a young man and the extensive education he enjoyed there, all for free — and he thinks about his brother, Aaron, who was a nephrologist in Argentina until his death five years ago. Despite their geographic distance, the siblings talked almost daily about medicine. Gerszten finds that he still carries his brother’s voice around in his head as he wrestles with an issue, most often related to public health, keenly missing the chance to discuss the topic with him.

Gerszten nearly pursued public health as his medical focus and it remains central to his thoughts. He says pathology has given him a sometimes troubling insight into the catastrophic results that come with a lack of access to health care. Over the years, he has seen up close how frequently deaths could have been avoided with earlier preventive care measures. He pores through public health research and considers how to solve the vexing problems the researchers are tackling.

He thinks about his old students, too. They’re never far from his mind. They’re spread out across the country, carrying his lessons with them. He might not be able to solve the world’s health challenges on his own, but he understands he has done more than his share to help fill the world with dedicated doctors equipped to pursue that mission.

“I love knowing they’re out there,” he says. “They’re everywhere.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.