Aug. 22, 2018

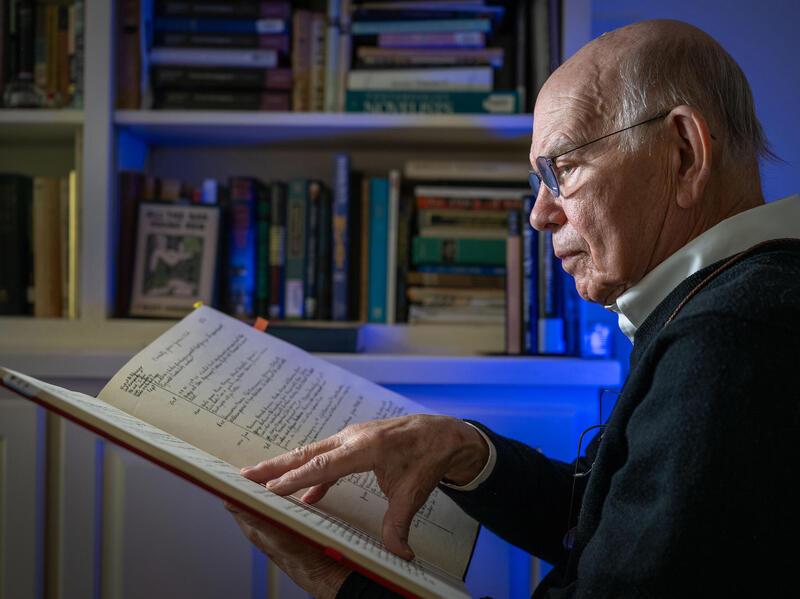

In ‘Gay, Inc.,’ VCU professor shows how nonprofit sphere’s expansion has helped — and hindered — the LGBTQIA+ cause

Share this story

The conservative turn in queer movement politics is due mostly to the movement’s embrace of the nonprofit structure, argues a new book by Myrl Beam, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies in the College of Humanities and Sciences.

In “Gay, Inc.: The Nonprofitization of Queer Politics,” Beam relies on oral histories, archival research and his own activist work to explore how LGBT nonprofits in Minneapolis and Chicago are grappling with the contradictions between radical queer social movements and their institutionalized iterations.

Beam discussed his new book, which was published by the University of Minnesota Press, with VCU News.

How would you describe the central argument of “Gay, Inc.”?

At its core, this book tries to explain a major shift in queer politics over the last half century. Though it often comes as a surprise to my students, marriage hasn’t always been the be-all and end-all of the LGBT movement. In the ’60s and ’70s, the LGBT movement was part of a broader set of interconnected revolutionary people’s movements, including those of people of color, like the Black Panthers and the American Indian Movement, the feminist movement, and the anti-Vietnam War movement.

The LGBT movement, at least a significant and significantly mobilized part of it, was explicitly leftist, anti-capitalist, critical of police violence, and was invested in resisting norms around sexuality. The idea of settling down, getting married and buying a house in the ‘burbs was anathema to them! So what happened to shift the movement so dramatically that now upholding norms around sexuality (like marriage, for instance) is the central goal? We now have a movement that is relentlessly corporate, cares more about inclusion in the military than what the military does, and is laser-focused on discrete policy wins to the exclusion of all else.

It’s hard to transform society when you rely on funding from those who benefit from society exactly as it is.

“Gay, Inc.” explores the why of this shift. What happened to shift the politics of the movement so dramatically? How could a movement that was so anti-assimilationist now have assimilation as its most central goal? I argue that the institutionalization of the movement into the nonprofit system was a major driver of this shift. Incorporation into the nonprofit form means that organizations are reliant on individual donors, government grants or private philanthropy. And as the movement has become more and more reliant on a small number of wealthy donors, as well as corporations and private philanthropy, the goals of the movement began to shift to be more in line with what those funders would prioritize. So, why marriage? Because rich people wanted it, ultimately, and they drove the agenda of the movement with their donations.

And this dynamic isn’t limited to the LGBT movement. It is something that all social-justice movements housed in the nonprofit form have to contend with. It’s hard to transform society when you rely on funding from those who benefit from society exactly as it is. Ultimately, this organizational form has been devastating to the progressive left in the U.S. as social justice movements are pressured into prioritizing the goals of people for whom the status quo largely works.

What led you to be interested in this subject? How did your background as an activist inform the work?

After I graduated college, I imagined myself going out into the world to join “the movement” for social justice, and I assumed that meant working at a nonprofit. I thought “the movement” and working in a nonprofit were synonymous. But my early work experiences told me a lot about what happens when social movements are housed in nonprofits.

My first job was at a domestic violence nonprofit that was based in the courthouse, working as an advocate for LGBT survivors of intimate partner violence as they navigated the legal system. Next I worked as a case manager with LGBT young people experiencing homelessness, first at a transitional living program and then at a drop-in center. The common thread at all of these jobs is that they addressed systemic inequality in a wholly apolitical way, as if homelessness or intimate partner violence could be ended by assisting the individual victims of it.

I was working in Chicago as tens of thousands of units of public housing were being demolished. What did the homelessness organization have to say about it? Not a peep. Why? They didn’t want to — couldn’t afford to — alienate their funders. And it certainly was not just me that was appalled and frustrated by this apolitical and individualizing stance. So many people that I worked with recognized the systemic roots of the issues we were dealing with and felt so frustrated and depressed by the inadequate responses of the organizations at which we worked.

Around that time a fantastic book was published by an organization called INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence. That book, “The Revolution Will Not be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex,” introduced a concept that changed the way I thought about my work: the “nonprofit industrial complex.” They used that term to talk about the collaboration between the state, private philanthropy, corporations and nonprofits that had come to control the organized left. That book spurred a fantastic set of conversations, and helped me frame the questions I ask in “Gay, Inc.”

You suggest that the nonprofit structure of the LGBTQIA+ movement has ultimately led to more modest, conservative politics that emphasize marriage and legal equality over other issues facing the LGBTQIA+ community, such as police violence, poverty, homelessness, immigration and welfare. What led to this?

The answer to that question lives partially in the history of the nonprofit system. The nonprofit form developed in the U.S. as a way to stabilize early capitalism and prevent those who were most ravaged by its inequalities from rising up and demanding a more equitable distribution of resources. The voluntary sector, what we call the nonprofit system, serves as what Janet Poppendieck calls a “moral safety valve” that normalized poverty by giving the illusion of effective action combating it. This culture of charity suggests that individual giving, rather than mass mobilization, is the way to alleviate suffering. It also suggests that the cause of that suffering is individual, rather than the product of state-supported capitalism.

So, at its core the nonprofit system was intended to entrench and buttress capitalism and a racialized status quo that blames individuals for their poverty. And on a concrete level, nonprofit organizations are reliant on the wealthy for their funding, whether individual donors, government grants, private philanthropy or corporate giving. Because they have access to funding, those individuals and corporations are also significantly over-represented on nonprofit boards of directors, which control key organizational functions like goal-setting and long-term strategy. These donors have amassed their wealth because the system works for them as it is. They may want to make things a bit better, but it’s unlikely that they want profound, revolutionary change. This is a structural limitation of the nonprofit form.

Now, when you put LGBT organizations into that institutional form, those structural limitations don’t disappear. The specific effects of those structural limitations on the LGBT movement have meant that mainstream LGBT organizations have shifted toward the goals prioritized by the wealthiest and most privileged members of the LGBT community, those that have the resources to be major donors on which those organizations rely for funding. Those donors, nearly all white, mostly gay men, some lesbians, are people for whom immigration, health care, police violence and homelessness are not pressing issues. They are insulated from those issues by their wealth and privilege. So despite the fact that those issues are important to the vast majority of the LGBT community, they aren’t the issues that LGBT organizations have prioritized.

Do you think the LGBTQIA+ movement can shift toward a greater emphasis on progressive politics? Is that possible within the nonprofit infrastructure you're describing?

That remains to be seen, ultimately. There are certainly organizations that absolutely have shifted toward a greater emphasis on progressive politics. Southerners on New Ground, for instance, which has a Richmond chapter, is an intersectional, anti-racist queer organization that right now is focusing on immigration and police violence. It’s a membership-based organization, which means that while it does receive grants from private philanthropies, the majority of its funding comes from small-time donors.

Another organization that is explicitly leftist is the Sylvia Rivera Law Project in New York, which offers legal services to trans people caught up in the criminal legal system. Its board of directors includes incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and it operates via a consensus decision-making process.

Other organizations include Communities United Against Violence, and FIERCE in New York, among others. These organizations have a few things in common: They recognize that the nonprofit system tends to push organizations toward more conservative goals, so they make intentional decisions about their organizational form. For instance, they make sure that the board of directors is comprised not just of wealthy individuals, but of people who are part of the communities most impacted by the issues they address: folks of color, low-income folks, trans people, incarcerated people in the case of SRLP [the Silvia Rivera Law Project]. They don’t accept any and all funding. They recognize that all funding comes with strings. In other words, they take seriously the politics of nonprofitization.

But there is a larger question here, which is the relationship between nonprofits and movements. We have tended to collapse the two, and I think that has led to anemic, risk-averse, and narrow movements. Movements that tend to take on short-term, “winnable” campaigns, court cases and electoral efforts, because they are easier to fund rather than work toward culture change, which is a project of generations. Nonprofits are useful and necessary, especially for providing services that enable people to survive the present. But they are not movements. I do think that there is a place for nonprofits in movements, but they cannot replace mass mobilizations. I think Black Lives Matter and even Occupy Wall Street are great examples of movements that have taken up the work of culture change rather than just policy change, and have really shifted the conversation on a deep level.

Nonprofits are useful and necessary, especially for providing services that enable people to survive the present. But they are not movements.

What do you hope readers get out of “Gay, Inc.?” What impact do you hope it has?

Ultimately, I hope that people take away the lesson that the nonprofit structure isn’t benevolent, or even neutral. It emerged out of a specific history and was always intended to entrench and enable a system that benefits the rich. Just because it is an LGBT or racial justice organization doesn’t erase that history or intention. So if organizations want to do progressive work, they must also resist their own structure, they must subvert the original intention of their organizational structure. It can be done, but it takes intention and commitment.

How does your book's thesis fit within the context of the Trump era, when a new Supreme Court majority appears likely and may jeopardize gains for marriage and legal equality for the LGBTQIA+ community?

This is a great question, because we find ourselves in perilous times. The election of President Donald Trump, the ban of transgender people from the military, and now the recent retirement of Anthony Kennedy has — rightly — made queer people desperately afraid that the limited legal protections we were afforded under President Barack Obama will vanish in a flash. And as a parent who has used marriage and second parent adoption to protect my family, I totally understand that fear. But the very fragility of those protections tells us everything we need to know — if they can be ripped away that easily, they weren’t transformative change to begin with.

Unsurprisingly, given the nonprofit dynamics I’ve outlined above, as these legal protections are increasingly under threat, mainstream LGBT organizations have doubled down on fighting for them. But is access to fighting (and killing or being killed) in Trump’s military really what the vast majority of transgender people need in order to live more safely, freely and justly? Is marriage and its legal, tax and estate benefits actually the most important thing to fight for when many, or most, of the LGBT community is facing the daily threats of violence, poverty and criminalization?

The Trump era has exacerbated the problems with the LGBT movement that the book critiques: The power of wealthy donors to set the agenda of the movement and the resulting narrowing of the goals of the movement to formal legal equality. And, I would suggest that this narrowing in fact contributed to the election of Trump, in large part because the contemporary LGBT movement has failed to generate a mass mobilization of queer people, in large part due to its failure to prioritize the kinds of issues that would generate such a mass mobilization: immigration reform, anti-poverty initiatives, progressive taxation, police violence and a host of others.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.