Dec. 5, 2007

Pastoral care at VCU Health System gives medicine a spiritual touch

Share this story

Walking through the busy corridors of Main Hospital of the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, Ben Horrocks could easily pass for a physician in his white lab coat.

As one of a handful of resident chaplains in the VCU Health System’s Pastoral Care Department, however, Horrocks has duties that are quite different from a physician’s.

The kind of services Horrocks and the other residents, interns and chaplains who staff the department offer are not so much of a medical nature as they are an emotional and spiritual nature, intended to console patients, families and the staff who serve them during troubled times.

“Being in the hospital can be a very traumatic, anxiety-producing experience under the best of circumstances, much less when you have overlays of family dynamics and different things,” Horrocks said. “Unless you’ve been at a Level 1 trauma center before and really dealt with the depth of pain and struggle and challenge, there’s really no way to prepare yourself for it other than to experience it.”

Like most of his colleagues, Horrocks has a seminary background, having graduated in 2005 from Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C., and worked as an associate pastor. These theological ties often lead many to presume pastoral care is merely a religious formality, but Horrocks said a chaplain’s role is not limited to being a religious figure.

“We’re not there to proselytize, (and) we’re not there to espouse one religion over another religion,” he said. “If a person has a negative reaction to us and they really haven’t met us, that probably means that it really doesn’t have anything to do with us personally.”

Instead, Horrocks said, patients and their families’ attitudes toward chaplains are shaped largely by “how they see us.”

A philosophy of compassion

In his 17 years of chaplaincy at VCU, Ken Faulkner, assistant professor and director of pastoral care, has come to see chaplains less as religious stewards than as spiritual counselors who try to offer guidance about life’s existential questions: What is the purpose of life, and what comes afterward?

“As chaplains, we try to be sensitive to the fact that people are wrestling with these questions,” Faulkner said. “The first thing we want to provide is a passionate listening presence. If we can’t do anything else, then we can at least provide a place where people can explore these questions and concerns, and express their fears and anxieties with someone who will not cast judgment upon them but will listen with understanding and compassion.”

Faulkner said a chaplain’s function is not to provide answers to deep questions about life and meaning, which easily become amplified in a health care setting, but “to make room so that people in a supportive relationship can come to their own answers (and) conclusions.”

This open-minded approach first gained traction in the early 20th century, when Anton Boisen, widely recognized as the forefather of hospital chaplaincy and clinical pastoral education, called on chaplains to be more benevolent in their care of others. The minister is remembered today for his concept that every person is a “living human document.”

Faulkner said modern-day chaplains still champion Boisen’s idea of the “living human document,” but the increasing complexity of health care is challenging the way they deliver their services.

“People are having to be much more proficient,” he said, “and the expertise and knowledge base required to function at an appropriate professional level is also magnified.”

Nevertheless, Faulkner said, “in the midst of a high-tech, high-science world, what we do is still fundamentally very human.”

An embracing space

As VCU grows and evolves, the Pastoral Care Department, which will celebrate its 65th anniversary in 2008, is growing and undergoing change, too.

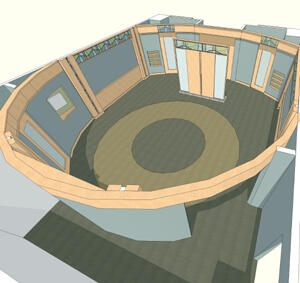

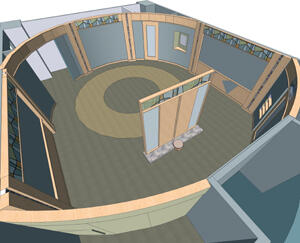

Most notably, the department plans early next year to renovate the focal point of its location at Main Hospital: the Main Hospital Chapel. Located between the pastoral care administrative offices and the director of nursing office suite, the modestly decorated chapel has not had significant enhancement since Main Hospital opened in 1981.

Ann Charlescraft, manager of Bereavement Services and a department chaplain, said the chapel plays a special role in the hospital.

“The chapel should be a place of comfort and solace for people in pain,” she said, “and a place of praise and thanksgiving for people who are grateful for the life they have.”

In keeping with the Pastoral Care Department’s interfaith, interdisciplinary outlook, Charlescraft said, the renovated chapel will accommodate visitors of all religious and spiritual orientations.

“If you walk into that space as someone just coming in for contemplative prayer, then what you will experience is a space that has the features of the earth,” she said. “You’ll have stone, wood, light (and) color. … The space will feel sacred, warm and embracing.

“There will be the sense of presence of something greater than ourselves but not necessarily tied to a particular religion.”

The department continues to raise money for the project, the design for which emerged from input from a committee of staff and community members. Given the community focus of the effort, the Pastoral Care Department decided not to solicit capital construction funds for the proposal.

When the renovation is complete, Faulkner said, the chapel will have added symbolic value as well as aesthetic value.

“One of the main emphases behind the chapel renovation is to make a statement about the respect and concern we have for the community we serve and the diversity of culture, religion and spirituality.”

Moving pastoral care forward

If the Pastoral Care Department is the face of chaplaincy at the VCU Health System, the Department of Patient Counseling, an academic unit within the VCU School of Allied Health Professions, is the engine behind it.

Consisting of various certificate programs and a master’s degree in patient counseling curriculum – the only one in the United States – the Department of Patient Counseling aims to provide its students, interns and residents with an educational experience that is equal parts theoretical understanding and hands-on learning.

“Our program is geared towards a certain teaching methodology,” said Alexander Tartaglia, program chair and associate dean for the School of Allied Health Professions. “We basically look at an action-reflection model of life that would provide students with a theoretical framework from which they can develop some intentionality about how they proceed as pastoral care providers.”

When Tartaglia was appointed department chair in 1996, his objective was to push the Department of Patient Counseling from a mostly certificate program to one whose emphasis is graduate study. Not only did the department implement a master’s degree curriculum since then, but it also added a track in patient counseling for the School of Allied Health Profession’s Ph.D. in health-related sciences.

Charlescraft said these academic developments, in addition to a committed engagement to research, give pastoral care an institutional legitimacy.

“An area that pastoral care has not engaged in sort of on the forefront is research in pastoral care,” she said. “Our program is helping to move the recognition of the necessity of research-oriented best practices in the profession.”

In recent years, the Department of Patient Counseling has received a number of research grants, which it has used to study organ donation and various end-of-life issues, among other topics. For many of these studies, the department has turned to other academic and professional disciplines to pool resources.

“Any research we do that’s going to be meaningful is going to have to be collaborative,” Tartaglia said.

As a student in the graduate patient counseling program, Horrocks is reflective of the department’s research advancement effort. Before he graduates in the spring, he plans to complete some independent study and special project assignments while he continues his resident chaplaincy.

After graduation, Horrocks said he intends to return to seminary to finish his ordination. Regardless of whether he goes on later to pursue chaplaincy in health care, he said his work and study at VCU have broadened his skills and afforded him the invaluable opportunity to comfort others during some of the most difficult moments of their lives.

One of the most touching cases Horrocks recalls involved a young college student who was in a car accident. As the teenager’s condition fluctuated, Horrocks stood by the teen’s family’s side. When it became clear the young man would not survive, Horrocks developed a special bond with the teen’s mother.

“She knew that he wasn’t going to make it,” he said. “Being there with her and praying with her and recognizing that this might be the last time that she might see her son alive … was a very sacred thing.”

Horrocks said such interactions have instilled in him a sense that no workday is the same as another.

“You can have this attitude, ‘Oh, I’ve been here for so many months or years, and I’ve seen it all,’ and that’s when something that you’ve never seen will happen,” he said. “You have to continue to have that open, humble attitude that you’re continually learning. While you’re growing and learning, you recognize there’s still so much more you can learn.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.