March 7, 2018

Three new genetic markers associated with risk for depression

Share this story

After becoming the first to definitively discover genetic markers for major depression, researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and collaborators have found more genetic clues to the disease.

A study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry details the discovery of three additional genetic risk markers for depression, which builds on the groundbreaking discovery of two genetic risk factors in 2015. Lead authors include Roseann Peterson, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the VCU Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, and Na Cai of the European Bioinformatics Institute and the Wellcome Sanger Institute in the United Kingdom.

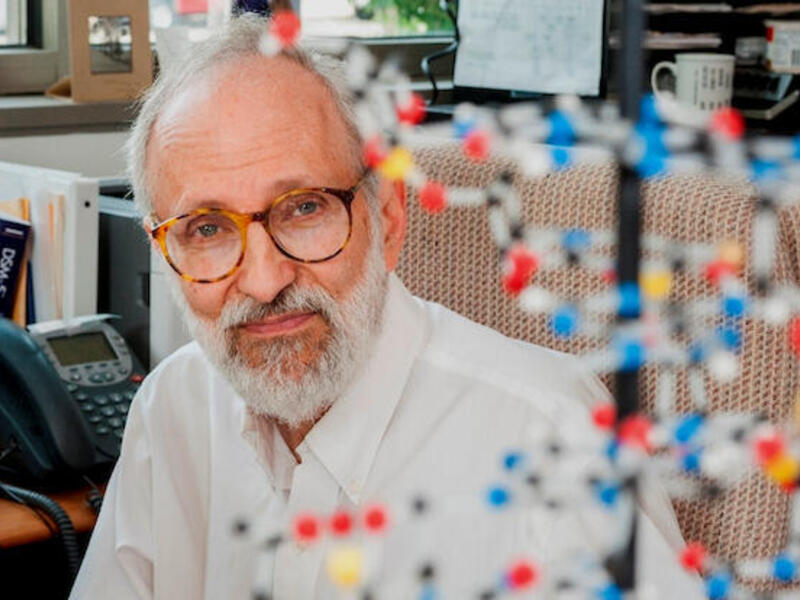

Both sets of findings were the result of an international collaboration among researchers from the Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, the University of Oxford and throughout China to shed light on genetic causes of the disease. Principal investigators Kenneth Kendler at VCU and Jonathan Flint at the University of California, Los Angeles led this large-scale collaborative effort, which resulted in a study of more than 10,000 Han Chinese women from 50 hospitals across China.

Initially, the researchers were able to isolate changes in DNA that increase risk for major depression and published a paper on the discovery in the journal Nature. The most recent findings take this a step further by determining that the additional genetic markers are relevant to the disease in a subset of people who have not experienced extreme adversity.

Kendler, M.D., professor of psychiatry and human molecular genetics in the Department of Psychiatry in the School of Medicine, and one of five VCU faculty authors, said the work could shed more light on subtypes of depression and their treatment.

“We have struggled for years using twin and family studies to try to understand how genes and environment interrelate in causing depression,” Kendler said. “This is the first study where we have been able to do this using molecular variants. This is an important advance in our understanding of this important, severe and common psychiatric disorder.”

The researchers collected information on environmental adversity measures from their subjects. Environmental adversity includes experiences of extreme stressful life events such as childhood sexual and physical abuse. Observing groups who were adversity exposed and non-adversity exposed allowed researchers to account for diverse causes of depression, or the disease’s etiological heterogeneity, in determining genetic causes, Peterson said.

“Identifying genetic risk variants for major depressive disorder has been difficult, likely due to associated clinical and etiological heterogeneity,” Peterson said. “Here, we highlight individual differences in clinical presentation and the importance of collecting symptom level data to tackle clinical and etiological heterogeneity in complex psychiatric traits.”

Peterson said the ultimate goal is to identify high-risk individuals for early intervention and personalized medicine. Cai said the discovery could lead to additional findings on potential links between metabolism and depression.

“Some of the genes implicated by variants we found to be associated with depression are involved in mitochondrial function and metabolism,” Cai said. “So, one potential direction for future research is to try to understand the link between depression and metabolism.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.