Dec. 14, 2017

VCU, Swedish study finds genetics and environment equally contribute to major depression transmission

Share this story

Parent-to-offspring transmission of risk for major depression is the result of genetic factors and child-rearing experiences to an approximately equal degree, according to a new study conducted by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Lund University in Sweden. The discovery is the result of the first large-scale adoption study of major depression.

The study, “Sources of Parent-Offspring Resemblance for Major Depression in a National Swedish Extended Adoption Study,” published Dec. 13 in JAMA Psychiatry, a monthly, peer-reviewed medical journal produced by the American Medical Association.

The finding that genetics and environment contribute equally to the transmission of major depression from parents to children contradicts previous findings, which have resulted from smaller-scale twin studies and have largely suggested that genetics play a larger role in the inheritance of depression than the child-rearing environment.

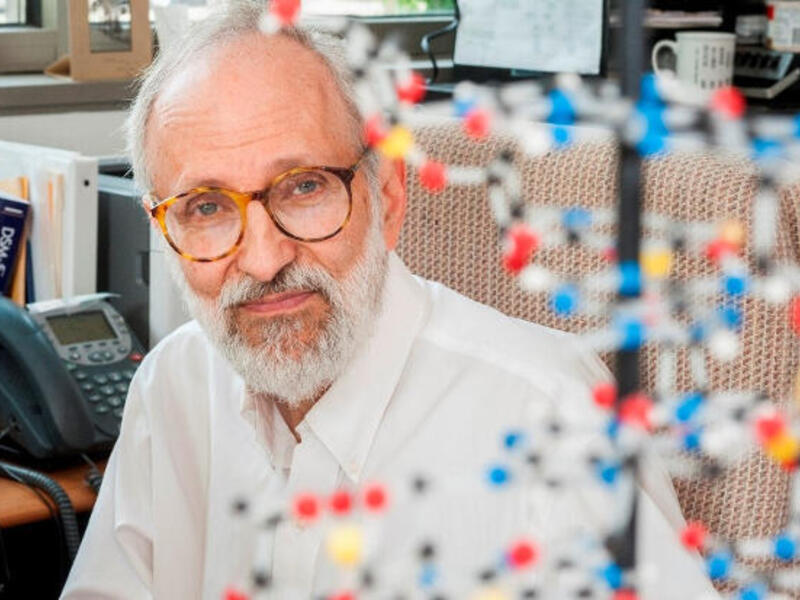

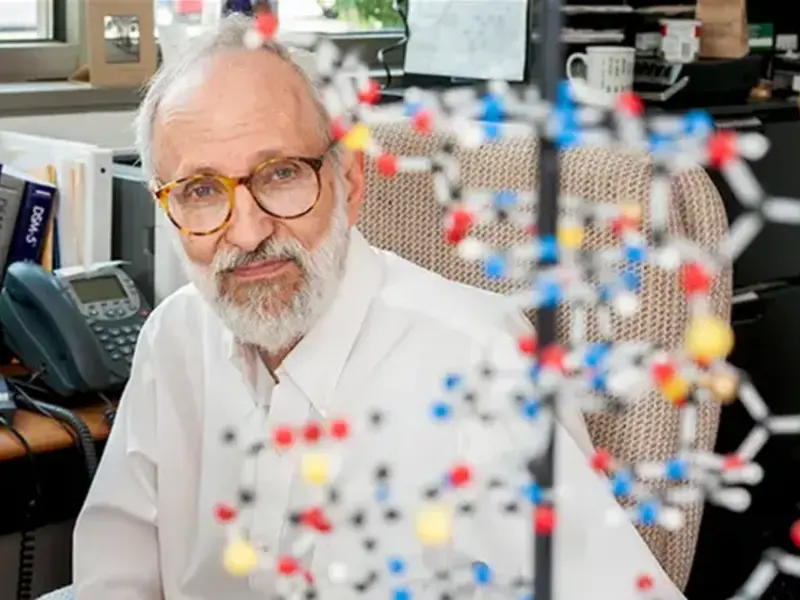

We have been too preoccupied with the role of genetic factors in the transmission of major depression,

“We have been too preoccupied with the role of genetic factors in the transmission of major depression,” said first author Kenneth S. Kendler, M.D., professor of psychiatry and human and molecular genetics in the Department of Psychiatry at VCU School of Medicine. Kendler added that the absence of a well-powered adoption study of major depression represented a large gap in the scientific understanding of the disease’s origins.

In the recent large-scale adoption study, VCU and Swedish researchers examined a representative sample of more than 2 million Swedish people to rate the degree to which transmission of major depression from parents to offspring was the result of genetic versus child-rearing effects. They also studied how genetic and child-rearing effects jointly contributed to the resemblance for major depression between parents and their children.

“The basic finding one gets from an adoption study is: How much do the biological parents who didn’t raise the child contribute and how much do the adoptive parents who aren’t genetically related but raised the child contribute?” Kendler said. “Those correlations were about the same in this study, suggesting that parents transmit major depression almost as much by how they rear children as occurs genetically, which is not what people would expect based on other studies.”

The key to the feasibility of the project was the availability of a large database of primary care registry data in Sweden. Most major depression diagnoses in Sweden are made by primary care doctors, Kendler said.

Major depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the U.S., according to the National Institutes of Health. In 2015, an estimated 16.1 million adults aged 18 or older in the U.S. had at least one major depressive episode in the past year. That number represented 6.7 percent of all U.S. adults. The disease also carries the heaviest burden of disability among mental and behavioral disorders in the U.S., according to the World Health Organization.

“There are significant things parents do that impact the risk for depression running across generations,” Kendler said. “We can’t intervene with genetic factors yet, but we can figure out why depression is being transmitted from parents to children and help parents reduce the risk of transmitting it to their kids.”

Kendler, director of the Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics at VCU, collaborated with Lund University researchers Henrik Ohlsson, Ph.D.; Jan Sundquist, M.D., Ph.D.; and Kristina Sundquist, M.D., Ph.D. Jan Sundquist and Kristina Sundquist also have affiliations with the Stanford Prevention Research Center at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

“Dr. Kendler’s skilled ability to facilitate international research collaborations among leading worldwide experts has advanced the global understanding of psychiatric diseases, which do not discriminate based on nationality,” said Peter Buckley, M.D., dean of the VCU School of Medicine.

Kendler’s previous international research breakthroughs include a collaboration among researchers from VCU, the University of Oxford and throughout China that led to the first identification of risk genes for clinical depression. He has also collaborated with colleagues in Sweden to elucidate motivations for drug abuse cessation and risks for alcohol use disorders.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.