June 30, 2021

A VCU-led study conducted early in COVID-19 could help confront the next health crisis

Share this story

In mid-March 2020, a team of researchers led by a Virginia Commonwealth University professor conducted a survey of 500 U.S. adults to investigate how likely they would be to adhere to preventive behaviors that were recommended at the time, such as not touching your face, social distancing, avoiding large gatherings and staying away from people who were sick.

The results of the study, “Stay Socially Distant and Wash Your Hands: Using the Health Belief Model to Determine Intent for COVID-19 Preventive Behaviors at the Beginning of the Pandemic,” published in the journal Health Education & Behavior, provide insights into how public health officials can encourage people to take difficult but potentially lifesaving preventive measures in future outbreaks.

“COVID-19 is not the last time we’re going to be confronted with infectious diseases. There’s a fairly good likelihood it’s not the last time we’re going to be confronted with a pandemic,” said lead author Jeanine Guidry, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Richard T. Robertson School of Media and Culture in the College of Humanities and Sciences and director of the Media+Health Lab at VCU. “Understanding how these things work in the beginning — even though it won’t be exactly the same because we have now had the experience of COVID — I think is going to be really helpful.”

When the survey was conducted March 16-18, 2020, COVID-19 was still emerging in the U.S. On the first day, there were 4,500 diagnosed cases and 88 deaths, and on the final day of the survey there were 7,100 cases and 141 deaths in the U.S. By the end of May 2021, there had been more than 33 million cases and nearly 600,000 deaths in the U.S.

The researchers asked the respondents: How likely are you to adhere to the following recommended COVID-19 preventive behaviors: social distancing, wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, avoid touching your face, avoid close contact with anyone who is sick, stay home when you are sick, cover your cough or sneeze with your elbow or a tissue, avoid large gatherings?

A majority of respondents said they were extremely likely to abide by the recommendations, ranging from 56.8% saying they were “extremely likely” to not touch their face to 74.2% saying they were “extremely likely” to follow hand-washing guidelines.

The results also found that women were significantly more likely than men to say they would follow the recommended COVID-19 preventive behaviors of social distancing, washing hands, avoiding touching their face, respiratory hygiene, staying home when sick, and staying away from sick people.

Additionally, non-Hispanic Black respondents reported significantly lower intentions to follow the recommended COVID-19 preventive behavior of avoiding large gatherings, as compared to non-Hispanic white respondents.

“That is concerning, particularly because at this point we had just started to learn that COVID-19 was actually affecting people of color in a more severe manner and more frequently than their white counterparts,” Guidry said. “Not just that we know now that they were more likely to be infected and get really sick, but they were actually less likely to carry out those behaviors in the early stages.”

“COVID-19 is not the last time we’re going to be confronted with infectious diseases. There’s a fairly good likelihood it’s not the last time we’re going to be confronted with a pandemic. Understanding how these things work in the beginning — even though it won’t be exactly the same because we have now had the experience of COVID — I think is going to be really helpful.”

Jeanine Guidry, Ph.D.

Paul Perrin, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Psychology in the College of Humanities and Sciences, was a co-author on the paper. The study’s findings, he said, are critical for illuminating various influences on people's adherence to COVID-19 preventive behaviors.

“Across all types of preventive behaviors, if people believed that a specific behavior could help prevent contracting and spreading COVID-19, they were much more likely to engage in that behavior,” he said. “As a result, public health campaigns that spread awareness of the health benefits of particular preventive behaviors may be the most likely to achieve their goal of increasing those preventive behaviors.”

The researchers investigated whether a widely used model guiding health communications in a crisis, known as the Health Belief Model, could predict whether different groups would adhere to COVID-19 preventive behaviors. The model is based on the hypothesis that as people fear diseases, health actions depend on the degree of fear (i.e., perceived threat) and the expected fear-reduction potential of those health actions. Its key constructs include perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers and self-efficacy (or a person’s confidence in their ability to perform an action).

“In the case of COVID-19 preventive behaviors, we operationalize perceived severity as how serious one perceives COVID-19 to be, perceived susceptibility as how vulnerable one perceived oneself to be to COVID-19, perceived benefits as the perceived advantages of the recommended preventive behaviors for COVID-19, perceived barriers as perceived obstacles to these preventive behaviors, and self-efficacy as one’s ability to carry out the preventive behaviors which are the focus of this study,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers used the Health Belief Model to test likely adherence to each of the recommended preventive behaviors. The model worked to predict at least some of the behavioral intentions, suggesting that the model would be useful for public health officials in crafting messages amid a crisis like COVID-19.

The results are a reminder, Guidry said, that health communication works best when public health specialists and communication specialists work in collaboration and incorporate tested theories like the Health Belief Model.

“You have to convince people that if you do this [action], you’re actually going to protect yourself and those you love against getting this disease,” she said. “And I think that just makes sense and it helps if you put messages together. Don’t just talk about, for example, ‘We’ve now lost X number of hundreds of thousands of people who’ve died of COVID.’ Also mention that we have effective ways to prevent it. That’s the lesson that we should learn in all cases.”

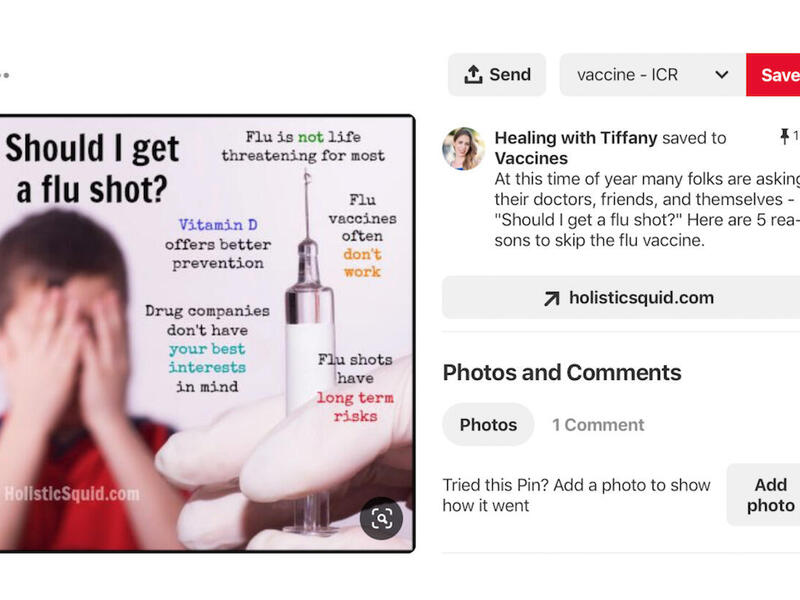

The study was supported by a grant from the Arthur W. Page Society. The grant originally was to fund a study on messaging around the flu vaccine, but the researchers asked to shift its focus to COVID-19 once the outbreak occurred.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.