Dec. 4, 2015

‘Best in Class’ teachers learn to pre-correct problem behavior

Share this story

Pop quiz: What’s the better way to ask a child in the classroom to stay in his seat when he keeps getting up?

A. “You need to sit down. I told you to sit down.”

B. “Hey, can you show me how you put your bottom on your seat? Can you show me that?”

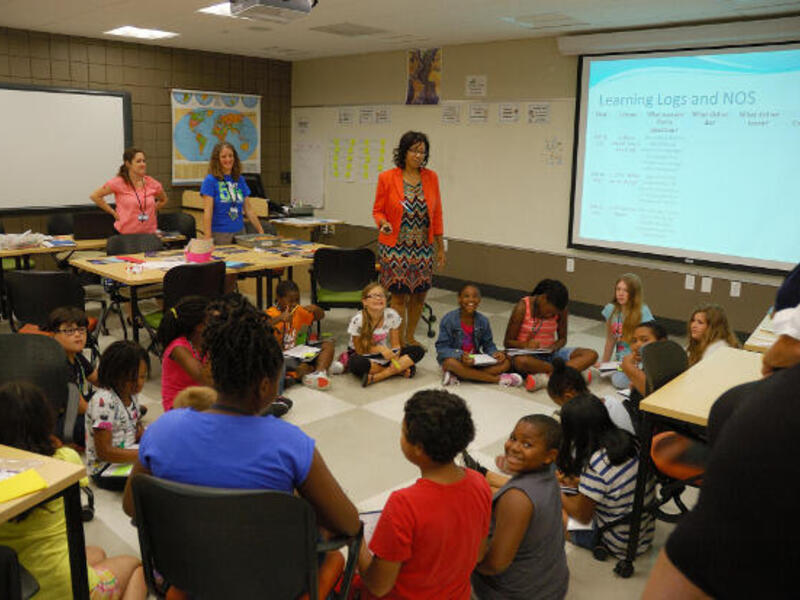

While the answer is easy when you see these options in black and white, that’s not always the case for an elementary school or preschool teacher managing up to 30 children at a time. A Virginia Commonwealth University project, “Best in Class,” trains teachers to pre-correct, to anticipate when there is typically problem behavior.

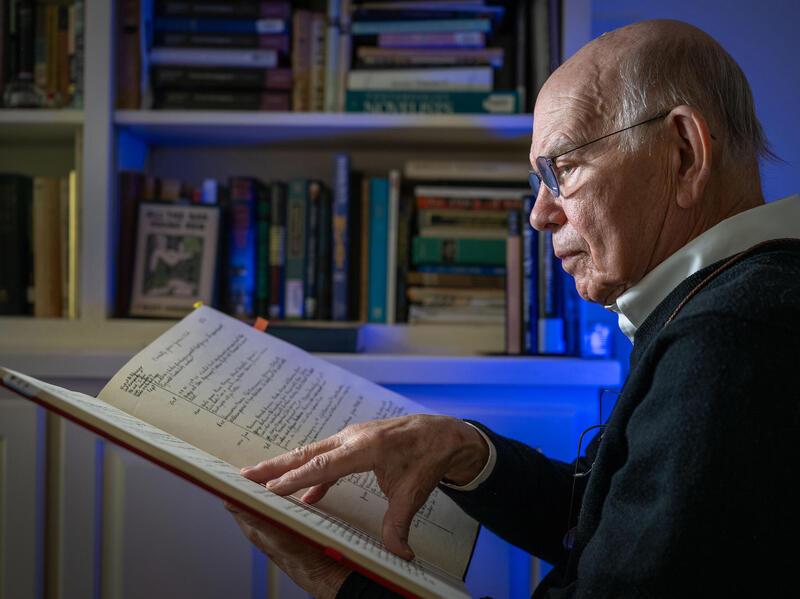

“If you know he always has problems picking up his toys for example, then before it’s time to pick up his toys, you walk over to him, maybe pat him on the back and you say, ‘Hey, it’s almost time to clean up. Remember, here’s what you do when you clean up,’” said lead investigator Kevin Sutherland, Ph.D., professor in the VCU School of Education. “We don’t want the teacher to stop correcting their mistakes. Because that’s how we learn. So we work with teachers on how to correct the children’s mistakes, particularly children that can be a little more volatile, have more problem behavior. But also how to give them more positive feedback, more praise when things go well.”

Sutherland and co-investigators Bryce McLeod, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychology in the College of Humanities and Sciences, and Maureen Conroy, Ph.D., the Anita Zucker Professor of Early Childhood Studies at the University of Florida, finished the first “Best in Class” project at preschools in August and are developing the next program for elementary schools. “Best in Class-Elementary” extends this intervention into early elementary school, allowing their team to adapt the program to better meet the developmental, behavioral and academic needs of K-2 students who exhibit problem behaviors. Investigators will adapt the intervention in year one, pilot test the intervention in year two and conduct a randomized controlled trial in year three in order to test the efficacy of the model.

“Best in Class” has existed in some form or another for nearly a decade, beginning with Sutherland and Conroy receiving a grant from the Institute for Education Sciences to develop an intervention for teachers to use in preschool classrooms for young children with chronic problem behaviors.

The project is a Tier 2 program. Tier 1 programs are considered universal prevention programs that all students receive. Sutherland likens it to fluoride that everyone gets through toothpaste or tap water.

“Tier 2 is what happens when you get a cavity,” he said. “You go to a dentist and you get work done. So from a behavioral perspective, Tier 1 interventions are supposed to be effective with 80 to 85 percent of children. What happens to those kids that don’t respond to that, that need more, that already are coming to school with problem behaviors for whatever reason?”

The team spent three years working closely with teachers and administrators to develop the “Best in Class” intervention for preschool teachers. They then received an additional IES grant to conduct a randomized control trial on that intervention. Over four years, the project has collected data on several hundred teachers and several hundred children — the latter group having been identified as having problem behaviors.

We’ve seen increases in improvements in student-teacher relationships and improvements in the overall classroom climate.

“We’ve gotten really good child outcomes, and teacher outcomes for that matter,” Sutherland said. “We’ve seen decreases in child disruptive behavior, increases in child engagement in school. We’ve seen increases in improvements in student-teacher relationships and improvements in the overall classroom climate. So essentially, through this intervention that involves training teachers in our intervention model, and coaching them to use the practices, we see some significant improvements in the classroom.

“We’re real excited about that and we’ll try to continue that project. But meanwhile, one of the things that came up earlier when we were recruiting teachers a couple of years ago, one of the preschool teachers says, ‘So what happens when my babies get to kindergarten? What are the teachers going to do because they don’t know this type of intervention?’”

That question led to Sutherland, Conroy and McLeod developing a proposal to IES that would extend “Best in Class” into elementary schools. Since elementary school classrooms differ greatly from preschool classrooms, the intervention is being adapted for the different contexts, expectations and training. It also must take into account the developmental needs of children who are not 4 years old anymore, but anywhere from 5 to 8 years old.

Eventually, Sutherland hopes “Best in Class-Elementary” can expand to follow these students longitudinally. At the end of the current three-year grant — assuming that they have developed an intervention that demonstrates some promise — he plans to apply for another grant to test the project in a larger efficacy trial. He’d like to follow the children into middle school and further to see if an intervention such as this, early in school, can have some longer term outcomes on children’s development.

Subscribe to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.