Sept. 14, 2020

'Symbolism matters': A look at the future of commemorations at VCU

Share this story

In Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy during the Civil War, symbols commemorating the Confederacy and the people who supported it have long been commonplace. Similarly, at Virginia Commonwealth University, the city’s urban university, commemorations that honor former Confederates have been a part of the campus landscape — from university buildings named after members of the Confederate army to statues in city-owned Monroe Park honoring those who served on that side in the war. However, those commemorations could soon become a thing of the past.

Following the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017, VCU President Michael Rao, Ph.D., charged a work group, the President’s Committee on Confederate Commemoration, with conducting an extensive audit of symbols of the Confederacy, racism, slavery, white supremacy and other items of an exclusionary nature that existed on VCU’s campuses. The step was prompted in part by students, faculty, staff and alumni raising concerns about the presence of these symbols at VCU. The work group subsequently engaged the university community, an eager participant in the process, in numerous interviews, presentations and small group forums.

That work led to the formation of the Committee on Commemorations and Memorials to make recommendations to approve memorials, commemorations and de-commemorations to the president. On July 7, the committee voted on 18 recommended actions and solicited public feedback. The committee received more than 3,000 comments on its recommendations.

The recommendations and public comments were shared with Rao on July 24, and he will make his recommendations to the VCU Board of Visitors at this week’s board meeting. The recommended actions include the de-commemoration of McGuire Hall, Baruch Auditorium, the Ginter House, the Jefferson Davis Memorial Chapel, the Tompkins-McCaw Library and the Wood Memorial Building — all spaces with namesakes who were members of the Confederacy. Recommendations also included petitioning the city of Richmond to remove the Fitzhugh Lee monument, the Joseph Bryan statue, and the W.C. Wickham monument in Monroe Park and the Howitzer statue near Park and Harrison streets. Each of the honorees had ties to the Confederacy. (The Monroe Park monuments and the Howitzer statue were removed this summer.)

“A commemorative landscape is a space held by a community to remember, celebrate, memorialize and honor people and events of the past with a significant impact on that community,” said Kathryn Shively, Ph.D., associate professor of history at VCU and a member of the Committee on Commemorations and Memorials. “At present, our commemorative landscape is dominated by symbols of the Confederacy, a country formed expressly to perpetuate slavery and white supremacy. Though the individuals represented in these statues and building names were complex people who existed within their particular historical contexts, their significant associations with the Confederacy and white supremacy during the Civil War, Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras prevail; their contributions cannot be extracted from the larger symbolic landscape of oppression.”

‘Symbolism matters’

Rao said a thorough study clearly demonstrated that the commemorations and memorials on the VCU campuses do not reflect the values of the university.

“Expert historical analyses reveal a more complete story of the meaning of all of these memorials and commemorations that we cannot ignore nor accept,” Rao said. “We have learned a lot from this process, and it is clear that the values represented by these namings and symbols run counter to the values to which we are committed — inclusion, equity and diversity. These Confederate honorifics are hurtful to people in our diverse VCU community, which now includes a student population that is nearly half minority and a patient population that is half minority and 40% African American.”

Although it can be easy to dismiss statues, plaques and other commemorations as “just symbols,” Aashir Nasim, Ph.D., vice president of institutional equity, effectiveness and success at VCU and chair of the Committee on Commemorations and Memorials, said it is important to recognize that “symbolism matters.”

Expert historical analyses reveal a more complete story of the meaning of all of these memorials and commemorations that we cannot ignore nor accept.

“For instance, taking down the dispiriting and vicious signs that read ‘Whites Only’ and ‘Colored Only’ from waiter sections, water fountains and waiting rooms mattered after Jim Crow segregation,” Nasim said. “That simple act helped to heal the psyche of a nation and also gave people a sense that we were making progress toward civil rights for all. In the same vein, removing Confederate symbolism from our campuses, which still yields a de facto segregation in terms of how that historical era gave rise to the education and health disparities we see today, may also serve as an opportunity for reconciliation and restoration.”

The committee’s recommendations are not solely about removing names. They also are about new commemorations. These include naming a School of the Arts building after Murry DePillars, Ph.D., who served as dean of the School of the Arts from 1976 to 1995, and removing the name “Harrison” from the current Harrison House to clear the way for the Department of African American Studies to commemorate and name the building.

“Our goal in this process was to begin to foster a commemorative landscape that reflects VCU’s values of diversity and inclusion, freedom, integrity and service,” Shively said. “In doing so, we work toward a community space in which all our members have the opportunity to thrive, learn, discover and create knowledge.”

The weight of history

The committee’s work included exploring the complexities of U.S. history and contending with sometimes varying interpretations of it. For instance, Nasim said a prevailing belief is that special consideration should be afforded doctors in the Confederate army. He said that line of thinking tends to argue that these individuals were conscripted and obliged to care for the war wounded. However, he said the committee saw no evidence supporting the narrative that doctors were conscripted to serve in the Confederate army, and some, in fact, were eager to enlist.

“Even more important, there is something to be said about the quality of care for Blacks enlisted in the Confederate army who did not see war but suffered disproportionately worse health care outcomes than white soldiers and even Black Union soldiers,” Nasim said. “Perhaps one of the reasons for this disparity in care is because of the superior nursing skills of Sally Tompkins [Tompkins-McCaw Library], who ran a private hospital, Roberson Hospital, to serve Confederate soldiers. Tompkins was commissioned by Jefferson Davis and became known as the Angel of the Confederacy and probably as close as you can come to being deified by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. One of the cruel ironies here about slavery and the Confederacy is that there never seemed to be any recompense for Black laboring and suffering. Someone like Sally Tompkins could be raised by an enslaved Black and run a hospital staff that included enslaved Blacks, but the quality of care and love for Blacks in the South, in general, including Black Confederate soldiers, specifically, was insufficient.”

Additional context into the post-war lives of former Confederates also sometimes showed evidence of a deepening of their white supremacist beliefs. For instance, Nasim pointed to Hunter Holmes McGuire, M.D., as a progenitor of eugenics, a debunked racist ideology based on pseudoscience and the supposed inferiority of Black and Indigenous people. Because of McGuire’s prominence as a physician and educator, his harmful ideas and convictions influenced not only his own medical practice but potentially the beliefs and practices of generations of physicians. Similarly, Nasim highlighted the decision by Simon Baruch, M.D., a Medical College of Virginia alumnus, Confederate surgeon and namesake of Baruch Auditorium, to join the Ku Klux Klan after returning to his native South Carolina as a form of insurrection or rebellion against the realities of Black Reconstruction.

Removing Confederate symbolism from our campuses, which still yields a de facto segregation in terms of how that historical era gave rise to the education and health disparities we see today, may … serve as an opportunity for reconciliation and restoration.

The activities of former Confederates sometimes had a lasting impact on the Richmond community and race relations. Nasim noted, for example, that figures such as James H. Dooley (Dooley Hospital), Joseph Bryan and Lewis Ginter all played roles in the development of a segregated Richmond.

“The monuments in the city of Richmond helped delineate the cultural, social and physical places and spaces that were considered off-limits to Black Richmonders,” Nasim said. “Many of these areas were planned by people who VCU has enshrined, such as James H. Dooley, who headed the West End Home Building Fund Company with Joseph Bryan. Yes, Dooley was known for his generosity and philanthropy, but he also actively participated in the construction of a segregated Richmond in the physical and political senses, especially if you consider his role in the disenfranchisement of thousands of Blacks post-Reconstruction because of their purported ‘political incompetence.’

“However, Dooley wasn’t alone. Lewis Ginter, also a Richmond-based philanthropist, and close business associate with James Dooley and Joseph Bryan, led the development of Richmond neighborhoods (Ginter Park) that were marketed as exclusively for white Richmonders. Notably, and not coincidentally, Ginter was a major benefactor and supporter of Confederate monuments in Richmond. Ginter had Confederate A.P. Hill disinterred from his grave and then financed the construction of a monument to him at the intersection of Hermitage and Laburnum Avenue.”

‘A path forward’

As monuments to the Confederacy and its key figures are removed from public spaces across the country — including on Richmond’s Monument Avenue — one recurring charge is that “history is being erased” with their removal. Shively said she believes it’s of the utmost importance to continue to study these individuals, the Civil War and their legacies — but that removing a statue or plaque does not amount to deleting history or attempting to forget it. In fact, the opposite is true.

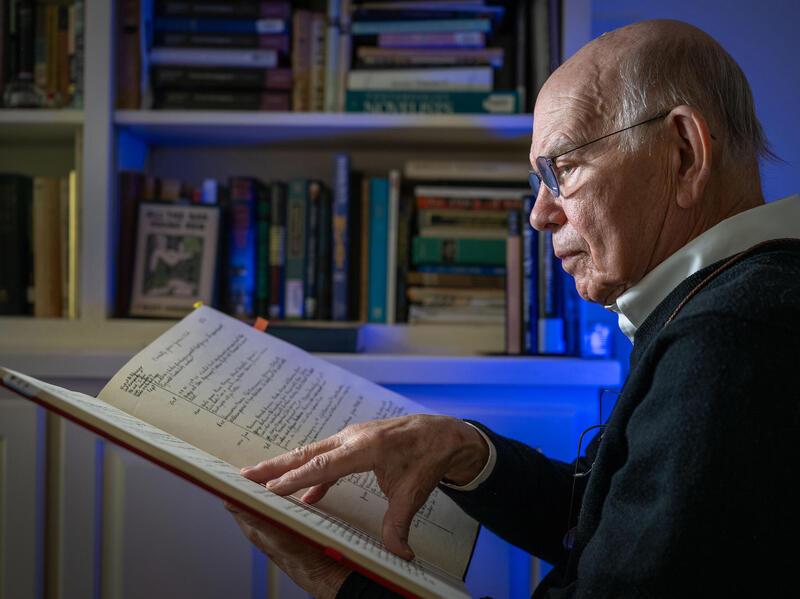

Shively said a challenge for the committee was educating the wider VCU community about the differences between history (what happened) and collective memory (how people remember the past to foster their shared identities) and how both function in this process.

“We are a scholarly community who seek knowledge and understanding of the past that satisfies our academic standards, meaning history that is robust, inclusive and well-documented,” Shively said. “And yet our current memorials are a part of collective memory, with little to no historical contextualization. They, instead, stand as celebratory.”

The display of celebratory symbols of the Confederacy and white supremacy without context does not promote knowledge, she said.

“It sends a message to our community that we are choosing to honor a short-lived country that seceded from our country, the United States, expressly to preserve the institution of slavery and white-dominated social order,” Shively said. “We do not seek to erase history; we will carefully document the removal of these objects and names for current and future study.”

Shively said she did not see weighing the contributions of the individuals to be the work of the committee. Instead, committee members worked with the community to consider the symbolism present in VCU’s campus memorials. Focus groups demonstrated that community members felt oppressed by memorials associated with the Confederacy and white supremacy. She said “we cannot parse out specific meanings” when considering memorials to those who embraced white supremacy, whether their lives also include positive contributions to society.

“All meanings are always present, and thus oppression is always present while these objects and names stand as memorials,” Shively said.

Students, faculty and administrators have identified some of these symbols, but there is much more work to do. Decommissioning symbolic displays of oppression is just one piece of a larger puzzle to create an inclusive community, she said.

Ultimately, Shively said, VCU’s work to contend with its past and commit to its future is only just beginning.

“Doing the work of inclusion is incredibly humbling,” Shively said. “This committee seeks a path forward that will create a welcoming, inclusive environment of learning, research and discovery for our whole community. We recognize that de-commemoration is a process and that we do not have all the answers. Still, our committee believes this is a necessary first step toward healing and recognizing the dignity and worth of our diverse community members.”

For more about the work of the Committee on Commemorations and Memorials and its recommended actions, visit https://inclusive.vcu.edu/public-comment/.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.