Oct. 8, 2018

How to survive the open office

Share this story

The debate for and against open offices has been waged for years. Some studies show that open office spaces increase collaboration, while others find they actually decrease face-to-face interactions among employees.

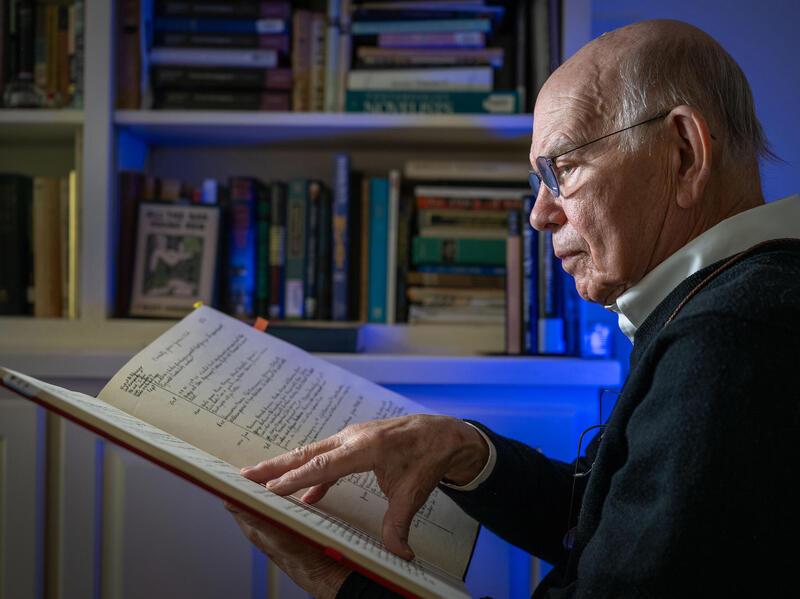

Christopher Reina worked in a cubicle once and hated it.

From an evolutionary perspective, humans used to avoid standing out in the open, said Reina, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Management in the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Business.

Not taking cover was “literally signaling you're out in the open ready for attack,” said Reina, who researches leadership and mindfulness. “Now, of course, it's not lions and tigers and bears anymore for us mostly, but it is bosses and leaders looking at us disapprovingly, or coworkers making judgments. We prefer to be shut away a bit.”

Reina spoke with VCU News from his office — one with a door — in Snead Hall about the phenomenon of open offices.

When did the open-office environment start to take off?

When teams started to become a new norm in business. We realized that people probably didn’t have all the information in their own minds, and skills that they needed, to best get something done. However, if you draw on the diversity of multiple people, then you can start reaching a solution that really is the best solution.

We know that when you bump into people more frequently, you share ideas with them. We also know that the more conversations with people you have, the more you tend to like these individuals. And if you like people more, you spend time with people more, you get to know people more and that creates what we call psychological safety.

When people feel psychologically safe, they share their ideas because they know they'll be valued, and then you're getting this sort of cross pollination of ideas, which leads to better solutions and a more innovative workflow. So when teams became a bigger focus, that's when we saw that move to more open office space.

How does an open office promote collaboration?

When you locate people together, there's this familiarity that you are helping them develop. We know that there's a startup cost every time we meet someone for the first time, whether that be a small startup cost, maybe like at a little cocktail mixer. But we can't meet everyone and we can't invest in everyone. And so we'll typically invest in the people closest to us. Open office spaces bring together a diverse set of folks into a small area in which you can get to know them. When you get to know them, you tend to like them more, and when you like them more, you're more comfortable working with them and know how to work with them better.

So collaboration, in theory, would increase the ability to draw upon the unique experiences and expertise of multiple team members. And it creates this sort of hum in the office, where everybody's doing their thing and there's this collective energy because people are feeding on the energy of each other.

What are the disadvantages?

The disadvantages deal with the fact that, as humans, we also need our own space. So this idea of self-monitoring is that we have to continually monitor our behavior in relation to the larger environment. If you think about it, now you're putting everyone in an open space so privacy goes away. Anytime you're drawing a focus and you're feeling like you could be watched, it actually, in the brain, suppresses to some extent your highest level of thinking because you're taking energy and resources from the task at hand to continually monitor the situation. Not necessarily monitoring for threats, but you can see the link there: “I'm doing my thing here, but there's also this larger environment that I’ve got to be watching and who's walking behind me, who's walking over there.”

The salience of people coming and going draws the eyes upward, draws the attention toward that person — which is inherently distracting. So while there are lots of positive things to the open office, there are also some drawbacks.

Then maybe I'm on task right now and I'm really in the flow, but you're sitting next to me and are in need of some new ideas; where you are in your project iteration is bringing in new ideas from your colleagues. You want to connect with me, but I want to do my thing, which creates a natural tension between the two of us. I don't want to talk to you right now, but you want to connect about ideas. So then you see some frustration there.

Plus, you're constraining humans' ability to be human. What if you're a loud talker and now you're taking a phone call in the middle of an office space? What if you don't know that you're a loud talker? Then you're making people mad, right? So that's a problem. If you are a loud talker and you know it, you're constraining yourself and then you're continually thinking “I can't talk too loud,” which takes you away from the call that you're having. So you're monitoring your behavior again. When you have all these layers of things going on, it can get in the way of the task at hand and performance in general.

How can someone use mindfulness to cope in this kind of environment?

If we're getting frustrated, we're interpreting the event in relation to ourselves. It's an ego-based response. And that happens whenever we get upset, whether there's someone who cuts us off or walks in front of us, or delays our ability to get to the grocery store line the fastest. Whatever it is, if we find ourselves tensing up and getting frustrated with someone, at the root of it, it has to do with a feeling that our goals or our something is under attack. Recognizing that is the first step. Something can be annoying, but it doesn't really need to mean anything for you. And when people say things and do things, just recognize that there's a lot that could be going on.

Individuals may not even mean what they're saying. They may not even know what they're saying. They might not even be aware of how it's coming across. Those are just three things I named off the top of my head and there are probably another five. So we are then interpreting their behaviors based on our own set of biases. Then when we come to a conclusion about what they mean, our idea could be so far away from what they actually think or intend to communicate. In reality, he or she, if you could come down to it, is probably not doing something to annoy you. And if they knew it was annoying, maybe 5 percent of the workforce who are jerks just would be like, “I know that's annoying. I'm a jerk, I'm going to do it.” But I'd say 95 percent of us would actually be embarrassed. I would never want to be someone who made others feel negative emotions at work.

What are other techniques that people can use to remain productive in an open office?

We've seen folks move to headphones, quite literally a physical signal of, “I'm busy, don't talk to me. I have my headphones in.” Of course this leads to all sorts of other problems because then they're not available. And then they're annoyed when someone does ask them a question because they’ve got to pull out the earphones. Plus, we have folks listening to music really loud, so everyone ends up hearing the music anyway, and this can be annoying.

I've seen a trend toward organizations using fly-by spaces where there's maybe five or six conference rooms that you can book for small blocks of time throughout the day. It helps you remove yourself from the situation, maybe to do an hour of focused work or 30 minutes to take a call. This way, you don't have to say, “Sorry, I can't talk right now,” to your co-worker, and rather, you let your schedule, your actions, your daily work flow signal to your colleagues, and take you physically from your open office location. Then people aren't making judgments about you for not being a team player or being too busy for them or for being antisocial or introverted — all the layers of bias we continually heap on each other. We create a structure that allows someone to remove themselves temporarily to get what they need done and not be rude in the process.

What would you like to add?

A lot of times in organizations, we say one thing but do something different. What I think leaders need to think about when they design office space is if everyone else lower than them in the organizational structure is in cubicles and they're in an office, this can be problematic. It's the special cultures and organizations that say, “No, everyone's going to be in cubicles or everybody’s going to get offices. Maybe we’re going to switch it up, maybe we rotate it.” There could be strategic and innovative ways to have everyone go through the same thing rather than just certain people. But the way we are structured, at least here in the U.S., is as you move up the ladder, you get more exclusive space, and it gets more windows and it gets a bigger area and your desk gets bigger.

So the idea is that as you reach the highest rungs of the corporate ladder, you're more likely to talk over people. You're more likely not to listen to people. You're more likely to be dismissive of people. You're more likely to be texting when someone's talking to you. If you're the lower-level employee, you're not going to do that in front of your manager, likely, but how often does your manager do that in front of you? So we see this sort of depersonalization of the people we work with as we move up the ladder. The office layout could be an extension of this same phenomenon — and it is only through mindful consideration of the structures and policies that we put into place in our organizations that we can ensure they don’t do more harm than good.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.