April 17, 2015

In the running: VCU RUN LAB teaches smarter running through science

Share this story

As Paige Fitzgerald prepared to race in her seventh Monument Avenue 10K last month, she bought a new pair of shoes she hoped would make her faster.

The Newton running shoes were recommended to the 47-year-old after tests showed she strikes the ground with her forefoot, just one of several details Fitzgerald learned through her visits tothe VCU RUN LAB.

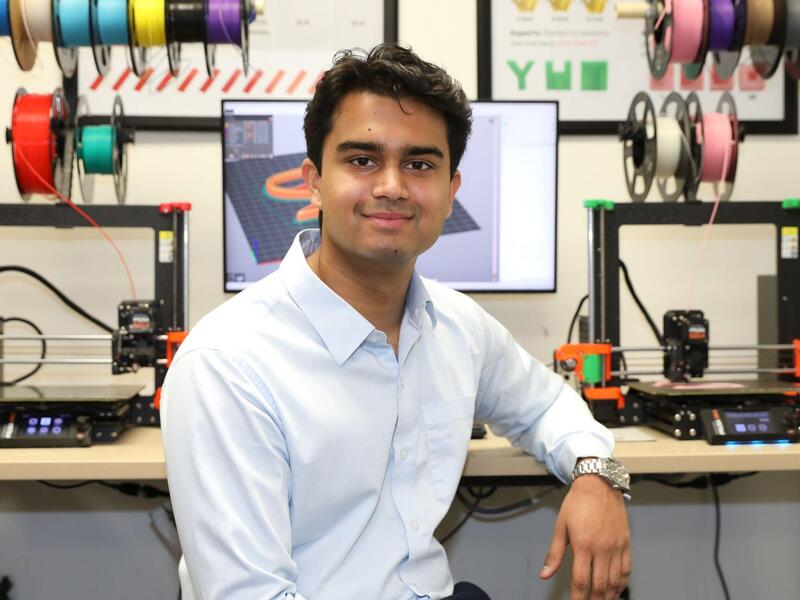

The lab is a collaborative project between the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Kinesiology and Health Sciences, part of the College of Humanities and Sciences; the Department of Physical Therapy, part of the School of Allied Health Professions; and Sports Medicine Clinic. It uses the latest technology to help people run healthier and, hopefully, faster.

A series of tests at the lab provided Fitzgerald a roadmap for how best to train and run, activities the local attorney once never thought she would be able to do.

Fitzgerald was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis in her 20s and had her left knee replaced in 2004. It wasn’t until 2008 that she entered her first 10K and walked. She entered more races, going faster each time, and eventually completed four half-marathons.

On March 28, she ran in her first 10K since visiting the VCU RUN LAB.

“I am hoping for a new personal record,” the local attorney said before the race. “Fingers crossed.”

‘The quality of human movement’

The VCU RUN LAB mixes biology and physiology, the personal and the clinical, and research and results. It’s a dynamic learning environment where student researchers can conduct studies that have immediate and direct impacts on the surrounding community.

Through precise measurements of heart, lung, muscle and joint function, the lab’s researchers can tailor advice on mechanics and training programs to every kind of runner.

“We’re a run lab, but we’re part of a much bigger mission related to the quality of human movement,” said D.S. Blaise Williams III, Ph.D., the founder and director of the VCU RUN LAB.

Williams and his team analyze the way knees and ankles bend and how torsos twist. They let people know that if they run with their feet facing out, like a duck, there is more stress on the inside legs and can cause pain in the front of the knee or just above the ankle. It also can lead to plantar fasciitis, a common cause of foot pain in runners.

People who run for leisure and exercise can describe what it feels like when they settle into a smooth, comfortable stride.

We try to take all of this science in the lab and translate it for people so they can use the knowledge in their day-to-day lives.

“They don’t recognize those moments in detailed terms of symmetry, torque, force and speed,” Williams said. “We try to take all of this science in the lab and translate it for people so they can use the knowledge in their day-to-day lives.”

Williams has spent the past 15 years studying runners, how they move and how they become injured. He came to Richmond from North Carolina in July 2013 and established the VCU RUN LAB in January 2014.

Williams views the human body as a spring with a weighted ball on top, like a bouncing lollipop. The differences between individuals and how they move means that, in the world of force, most people fall somewhere between the bounciest ball and an object so stiff its momentum is swallowed up by the ground on contact.

“It’s fine if I know how runners get hurt by viewing them as a spring,” Williams said. “But they can’t see it that way. They go home and run on the weekends with friends for fun. When something is fun, you want to do it more often. There are all kinds of metrics related to how many miles they run, intensity, pace and more that we have to look at so we can break it down for them.”

Williams is a licensed physical therapist and trained in three-dimensional biomechanics. He also is a seasoned runner.

In a city brimming with runners and races, that last point is not lost on those who have come to the VCU RUN LAB seeking advice.

It’s a big reason why Chuck McBride, leader of the Richmond Rogue Runners group, decided to participate in tests at the lab.

McBride, 48, has run countless 5K and 10K races, some half-marathons and 11 marathons. Still, it wasn’t until he visited the VCU RUN LAB that he discovered weak supporting muscles around his right hip.

Researchers conducted a gait analysis for him and produced a report full of recommendations “in a language that I understood,” said McBride, the president of an information technology company. “I have improved my right hip’s strength, and I feel more confident than I have been in the past.”

Inside the lab

The Run Lab is located on Grace Street in the Department of Kinesiology and Health Sciences building. The lab’s basic layout belies the rare technology researchers have at their disposal.

In the middle of the floor are two force plates. People run across the room and step on the plates or cut to change direction on them or simply stand and jump on them. Surrounding the two plates are 12 high-speed cameras.

Toward the back of the lab is a state-of-the-art treadmill from Treadmetrix that researchers use to study human locomotion. The VCU RUN LAB is one of just 13 customers around the world with such a treadmill, according to the company’s website. Five cameras stay trained on the treadmill, which operates at speeds up to 25 mph on inclines up to 25 percent.

The equipment helps researchers measure everything from maximum oxygen consumption to muscle strength and flexibility in the hips, knees, ankles and feet.

Normally, this kind of high-tech operation is reserved for elite athletes. The VCU RUN LAB seeks to bring the science to the masses.

“We can do that here in Richmond, because there are so many runners here,” Williams said.

VCU’s athletic teams—including track, basketball, soccer and lacrosse—use the lab to conduct pre-season and other tests. But so do other students, patients referred to the lab by doctors and members of the community such as Fitzgerald and McBride.

Inside the lab, subjects will wear markers, or sensors, on their hips, upper legs, lower legs and feet. The cameras above shoot infrared beams at these markers, which reflect light back into the cameras to define specific points in space as runners move their bodies.

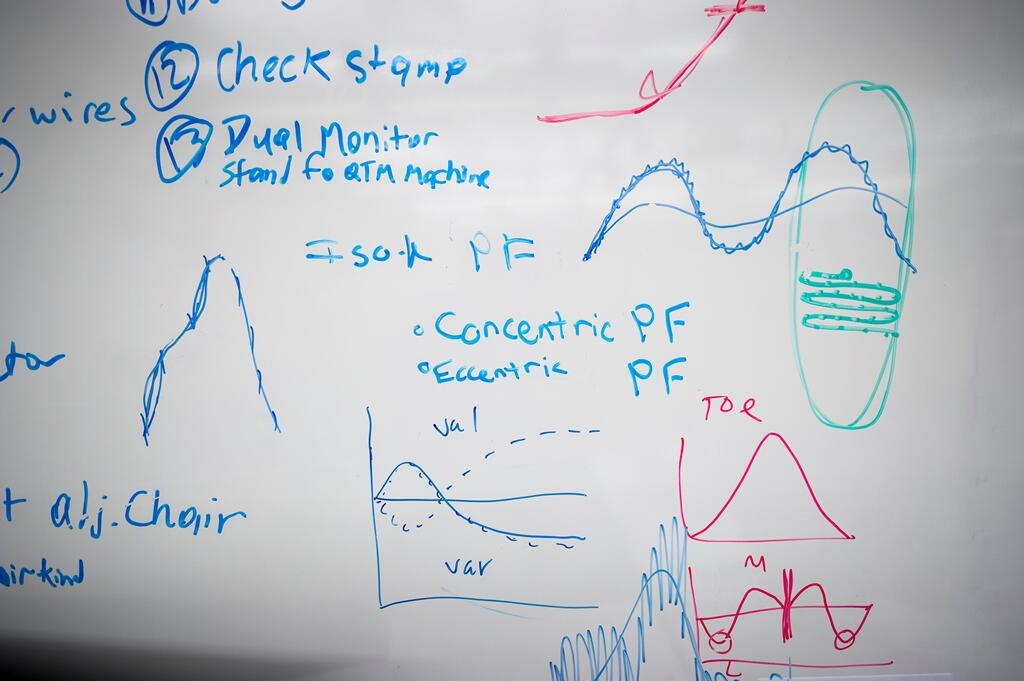

Software programs then go to work on advanced mathematics, a mix of trigonometry and calculus that creates charts and graphs. One program uses data from the markers to overlay a 3-D bone structure on a full-motion graphic depicting a runner’s movement.

Reports are generated that break it all down, taking into account three planes of movement and six measures of symmetry.

“You have increased Left and increased Right Pelvic Tilt at mid-stance,” the report given to McBride states.

Pelvic tilt refers to how much a person’s belly button faces down while running. It could be related to tight muscles on the front of the hips or in the lower back. It could also be the result of weak abdominal muscles, which support the front of the pelvis. An anterior pelvic tilt can lead to dysfunctional hip muscles if not corrected.

After having his strike positions and gait analyzed, McBride plans to return to the VCU RUN LAB for two more studies—one to determine his overall fitness and another to examine his nutrition level.

Something for everyone

VCU RUN LAB states its goal is helping people “run better.” That means something different to everyone.

For some, it means running faster. For others, it means being able to run without getting hurt.

For some, like former University of Richmond and Washington Redskins running back Tim Hightower, it means getting back on their feet after an injury.

Hightower is one of several athletes who have taken advantage of the VCU RUN LAB’s data-driven environment while rehabilitating from an injury. In Hightower’s case, it was to an anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL.

A collaborative grant with researchers from Virginia Tech is being submitted that will allow the lab to further study the symmetry and movement of patients who have had surgeries to correct ACL injuries just six months prior.

But even in a group with similar injuries, there are differences in every runner.

We try to take an individual approach with all the runners we see. We try not to make the same runner out of everyone.

“We try to take an individual approach with all the runners we see,” Williams said. “We try not to make the same runner out of everyone.”

While every case is different, there are some common running mistakes, Williams said.

Training errors such as running too much and overusing your muscles and joints is probably the most common. Along the same lines, running when tired or starting to train too soon after an injury can spell bad news.

The technology in the lab allows researchers to get inside of the science, reconciling the amount of exercise with how it’s being carried out biomechanically.

“I’m in the position where I go out waving the caution flag and telling people that they’re going to get injured if they run too much or with poor mechanics,” Williams said. “On the other hand, I get to tell them that the benefits far outweigh the risk of injury.”

He points to a recent study that found running just five to 10 minutes at slow speeds each day can lower your risk of death and cardiovascular disease. A paper describing the research equates not running with smoking, obesity and hypertension.

Running is an affordable and accessible way for most people to exercise, and most everyone can transition smoothly from a walking regimen to running, Williams said.

Fitzgerald is a perfect example of that.

“I know I’ll never be ‘fast,’ but I wanted to see what, if anything, I could do to go a little faster due to my limitations,” Fitzgerald said. “I am not anywhere close to being a superstar athlete, but [the VCU RUN LAB’s researchers] treated me as though I was one.”

The VCU RUN LAB has the same goal for everyone, from students to local residents and from those who run for leisure to marathoners and premier athletes, Williams said.

“We want to keep people out there running in a healthy way,” he said. “And if I have to go out there and grab them to get their attention, that’s what I’ll do. I’ll chase them down.”

If recent race times are any indication, at least some of VCU RUN LAB’s clients could make that chase more challenging than before.

McBride set a personal record on March 22 in the Shamrock Marathon in Virginia Beach, running the 26.2 miles in just over 3 hours and 22 minutes.

Just the day before, Fitzgerald ran a personal best in the Richmond SPCA’s Dog Jog and 5K Run.

As if to illustrate the constant struggle to run better and faster, however, the next week at the Monument Avenue 10K, Fitzgerald missed setting yet another personal benchmark by a few seconds.

“Next year,” she said afterwards. “Next year, I’ve got this.”

Subscribe for free to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday. VCU students, faculty and staff automatically receive the newsletter. To learn more about research taking place at VCU, subscribe to its research blog, Across the Spectrum at http://www.spectrum.vcu.edu/

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.