Oct. 12, 2010

International Research Team Uncovers How the Deaf Have Super Vision

Share this story

Ever wonder how it is that people who are deaf or blind seem to have enhanced perceptual abilities in their remaining senses?

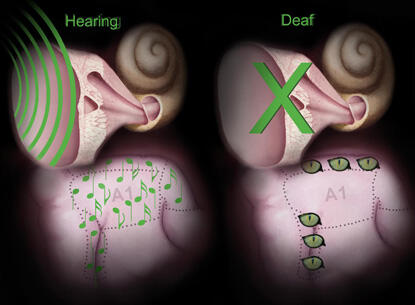

A new study by an international team of researchers may have uncovered how the part of the brain used for hearing is reorganized to enhance vision in congenitally deaf cats.

This phenomenon is known as cross-modal plasticity, which refers to the replacement of a damaged sensory system by one of the remaining systems. In this case, the sense of hearing is replaced with enhanced vision.

Although cross-modal plasticity is known to account for enhanced abilities in the replacement modalities, very little is known about the neurological basis of this compensatory effect.

In a study published online Oct. 10 in Nature Neuroscience, Alex Meredith, Ph.D., professor in the Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology in the VCU School of Medicine, together with principal investigator Stephen Lomber, Ph.D., with the Centre for Brain and Mind at the University of Western Ontario in Canada, and Andrej Kral, M.D., Ph.D., with the Medical University Hannover in Germany, examined the brain regions in congenitally deaf cats responsible for cross-modal plasticity after deafness.

Through a series of behavioral tests, the team found that the congenitally deaf cats had better peripheral vision and motion detection abilities than cats with normal hearing. Next, using a method of reversible deactivation, which involves temporarily chilling the brain through a surgically implanted tube, restricted parts of auditory cortex were silenced during those same behavioral tasks.

According to Meredith, when the parts of auditory cortex involved in peripheral hearing were cooled, the deaf animals lost their peripheral vision advantage. Likewise, when the area of the brain normally involved in detecting movement of sound was deactivated, the deaf animals performed no better than normal cats in visually detecting motion, he said.

Four other forms of visual processing were also evaluated, but showed no enhanced effects in deaf animals nor were they affected by cooling procedures.

“These results showed, for the first time, that cross-modal plasticity does not randomly distribute across the areas of the brain vacated by the damaged sensory modality, but instead takes up residence in areas that would normally perform a similar function,” Meredith said.

“For deaf humans, this explains why some visual skills get better while others do not change at all,” he said.

Ultimately, the team hopes this knowledge may guide the development of a new next generation of cochlear implants that will be better suited to the cross-modally reorganized brains of deaf patients. Cochlear implants can restore hearing in people who become deaf.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Last year, in related work, Meredith and a VCU team discovered that adult animals with hearing loss re-route the sense of touch into the hearing parts of the brain. Those findings provided insight into how the adult brain retains the ability to re-wire itself on a large scale, as well as the factors that may complicate treatment of hearing loss with hearing aids or cochlear implants. The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.