Oct. 31, 2018

Lab 3D scans human skeletal remains dating back to the Civil War

Share this story

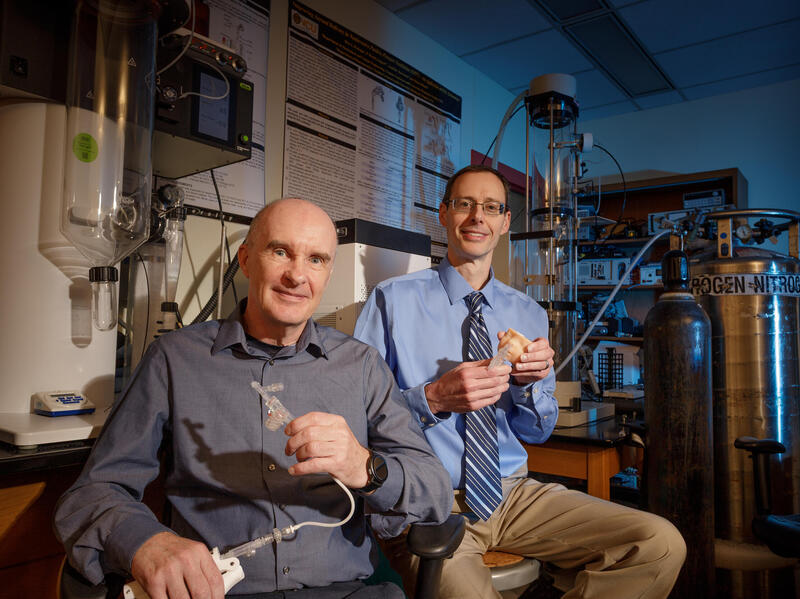

In the Virtual Curation Laboratory, the lab’s director, Bernard Means, Ph.D., is holding a realistic-looking 3D printed replica of a human skull fragment that was dented by a bomb explosion during the Civil War.

“For the rest of this person's life, they had seizures because of the [injury],” Means said. “In fact, they died because they fell into water during a seizure and they drowned.”

Means 3D scanned the skull fragment during a recent visit to the National Museum of Health and Medicine as part of an agreement with the museum to 3D scan items, primarily historic bone specimens, from the Civil War through World War I.

The museum, located in Silver Spring, Maryland, was established during the Civil War as the Army Medical Museum, a center for the collection of specimens for research in military medicine and surgery.

VCU’s Virtual Curation Laboratory specializes in the 3D scanning and 3D printing of historic and archaeological objects, and is part of the School of World Studies in the College of Humanities and Sciences.

So far, Means and his students have scanned and printed replicas of roughly 30 items in the museum’s collection.

Among the highlights are a leg bone that healed poorly after being shot during the Civil War, a skull with a hole in it from a Civil War surgeon’s trepanation procedure, a mummified ear attached to a skull fragment that was donated in the early 1900s, and a late 19th-century skeletal hand with a bullet hole from an area in the Midwest designated for Native American resettlement. None of the remains being 3D scanned is Native American.

“In the National Museum of Health and Medicine’s collection, they have pathological specimens of people who were injured in combat, going back to the Civil War. Some of whom survived, some of whom did not,” Means said. “It is one of the best collections of battlefield trauma specimens in the world.”

By 3D scanning items at the museum, the Virtual Curation Laboratory is aiming to make the collection more accessible to researchers and the public.

“They want to get 3D scans of items in their collection and they want to get them out there so the public can see them and also so that researchers can access them,” Means said.

For public programs, 3D printed replicas allow visitors such as school groups to get a more hands-on experience with a museum’s collection, he said.

“If a school group visits, [the museum] can't pass around human skeletal remains,” he said. “But they can pass around 3D printed replicas.”

The collection is of particular interest to researchers focused on the history of battlefield trauma, as well as forensic anthropology.

Terrie Simmons-Ehrhardt, a researcher in the Department of Forensic Science who studies forensic anthropology, specifically in forensic craniofacial identification and 3D osteology, has been collaborating with Means on 3D scanning bone specimens with a goal of creating a digital forensic osteology collection that would be accessible to anyone doing forensic research or education.

“I am assisting Bernard with the surface scanning of NMHM osteological specimens and also assisting the museum with processing of micro-CT and CT scans of some specimens,” Simmons-Ehrhardt said. “We are generating high-resolution 3D models to be shared online that can be interacted with either online or in 3D software, as well as 3D printed.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.