July 16, 2007

New method to create nanomaterials discovered

Share this story

On their path to developing chemical sensors for detecting bioterror agents, two Virginia Commonwealth University scientists discovered a new method for creating nano-sized polymer fibers that could be useful to engineers working to enhance microelectronics, filtration, drug delivery and tissue engineering.

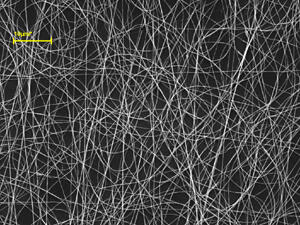

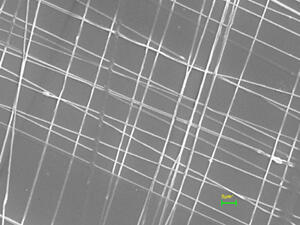

Polymer nanofibers can be created through a technique known as electrospinning, which uses electrical forces to produce inherently unstable fibers and nonwoven materials. By altering this process, Gary Tepper, Ph.D., a professor of mechanical engineering in the VCU School of Engineering, and Soumayajit Sarkar, a doctoral student, were able to produce stable, woven and aligned fibers — characteristics necessary for creating microchips for chemical sensors.

The new method, called biased AC electrospinning, allowed Tepper’s team to control and manipulate the polymer fibers into aligned arrays.

“If these fibers are to be used on a microchip to make chemical sensors, or in other applications such as tissue engineering, we have to control where they go. We can’t just be happy to make them and let them go anywhere,” Tepper said

For years, researchers in the microelectronics industry have worked diligently to create tiny, complex circuits or microchips from inorganic materials such as silicon. However, in chemical sensing, the challenge has been to marry those complex inorganic circuits with an organic material, which according to Tepper, is much more difficult to produce and control at the nanoscale. Using biased AC electrospinning, merging an organic component and a microchip may soon become a reality.

“For chemical sensors, response time is a big factor, particularly for nasty chemicals,” Tepper explained. “These things are extremely lethal and fast responding in the body, so the sensor has to respond faster than the body.

“Therefore, we need to make fibers, films or particles that are very, very tiny so that when they sense the vapor, the properties change instantly — the microchip detects those property changes — and conveys that into a signal,” he said.

Although tangled, nonwoven nanofibers have been useful in the past, there is a limit to their usefulness, said Tepper. For example, tissue engineers can use nonwoven, unstable fibers to replicate some of the body’s tissues. However, the nonwoven, unstable fibers do not work in the construction of an artificial human cornea. The scaffolding of this structure is composed of aligned, collagen nano-fibers in order to serve its purpose: transmitting light. According to Tepper, that is only possible if researchers can control the structure and orientation of those fibers.

Previously, researchers have attempted to control the instability of the nanofibers by applying lenses, external fields and a host of contraptions to the electrospinning device, but Tepper and Sarkar’s biased AC electrospinning is unique because it’s built into the process.

“Instead of applying the direct current (DC) potential we are just changing the kind of potential we apply to produce the fibers rather than use some external apparatus to try to suppress this instability,” Tepper said.

By biasing the alternating current (AC) potential, or amplifying the AC voltage, after using a variation of AC and DC potentials, the team was able to produce more uniform fibers with a higher degree of alignment.

Tepper will continue to focus on creating chemical sensors. “The technique we’ve developed is so useful in other things that it’s tempting to go and play around in these other areas that I’m really not that familiar with just to see what we can do,” he said.

Sarkar is finishing his doctoral studies this summer and in the fall is headed for the University of Akron in Ohio.

The study was published in the May 2 issue of the journal Macromolecular Rapid Communications. Seetharama Deevi, Ph.D., from Philip Morris USA contributed to this work.

This work was supported in part by a grant from Philip Morris USA.

For more information, visit http://www.engineering.vcu.edu/Microsensor/.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.