Oct. 26, 2015

VCU receives $4.2 million grant to study placental function in pregnant women

Share this story

The National Institutes of Health recently awarded a $4.2 million grant to Virginia Commonwealth University to study placental function in pregnant women and to develop a noninvasive device for the early detection of placental disorders such as pre-eclampsia.

The grant is part of the NIH’s Human Placenta Project, a collaborative research effort that would revolutionize the understanding of the placenta’s role in health and disease. Previous studies of the placenta have looked at the organ after delivery. This study will examine the placenta in real time, while it is doing its job.

The goal of this study is to be able to track pregnant mothers longitudinally, starting from when she goes to the doctor to confirm she is pregnant and throughout her pregnancy.

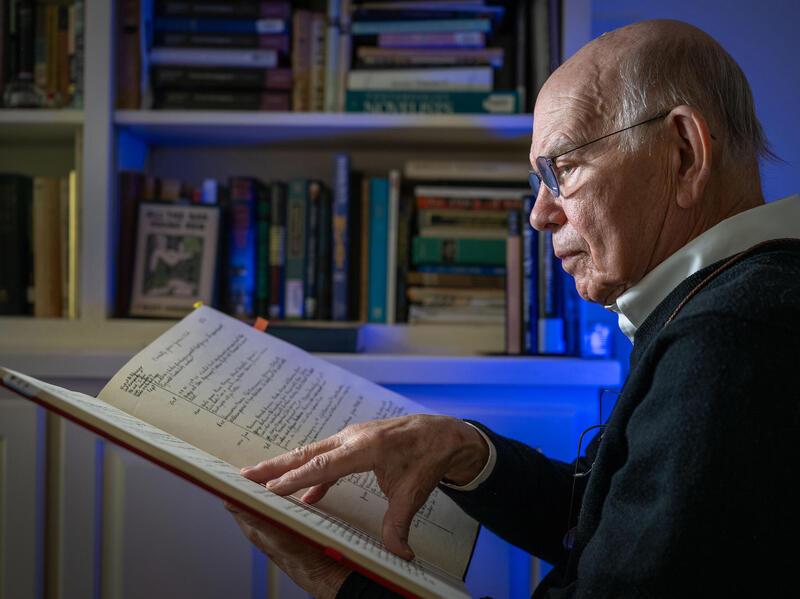

“The goal of this study is to be able to track pregnant mothers longitudinally, starting from when she goes to the doctor to confirm she is pregnant and throughout her pregnancy,” said Charles Chalfant, Ph.D., professor and vice chair of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in the VCU School of Medicine, and recipient of the four-year grant for his project, “The Utilization of Photonics Technology to Rapidly Detect Bioactive Lipids Associated with Pre-eclampsia Development.”

Five to seven percent of all pregnancies are affected by pre-eclampsia, a complication marked by high blood pressure and possible damage to other organ systems and the baby. Older and obese women, mothers carrying multiple babies, and those with pre-existing hypertension have a higher risk.

There is no cure for pre-eclampsia other than delivery, which can sometimes lead to preterm birth and a host of other complications. There are also long-term effects, such as an increased risk for heart disease for mothers later in life. Early detection is essential.

“What we’re hoping to do is to track and determine very early on, even before the clinician diagnoses the condition, which patients are going to have a placental disorder and which ones are not,” said Chalfant, project lead for the research team, which includes Scott Walsh, Ph.D., professor of obstetrics and gynecology and reproductive biology and research at the VCU School of Medicine; Dayanjan Shanaka Wijesinghe, Ph.D., assistant professor, Department of Pharmacotherapy & Outcomes Science, at the VCU School of Pharmacy; and Philippe Girerd, M.D., associate professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

During the first phase of the study, the clinical team led by Walsh will track patients at the high-risk clinic, where 50 percent of patients will have some kind of placental disorder. The team will look at patients on the biochemical level, specifically their bioactive lipids, a type of hormone that goes into dysregulation as a result of pre-eclampsia. The team will also determine if the problem is coming from the mother or the placenta, and all the data will go toward refining a lipid “fingerprint” specific to pre-eclampsia.

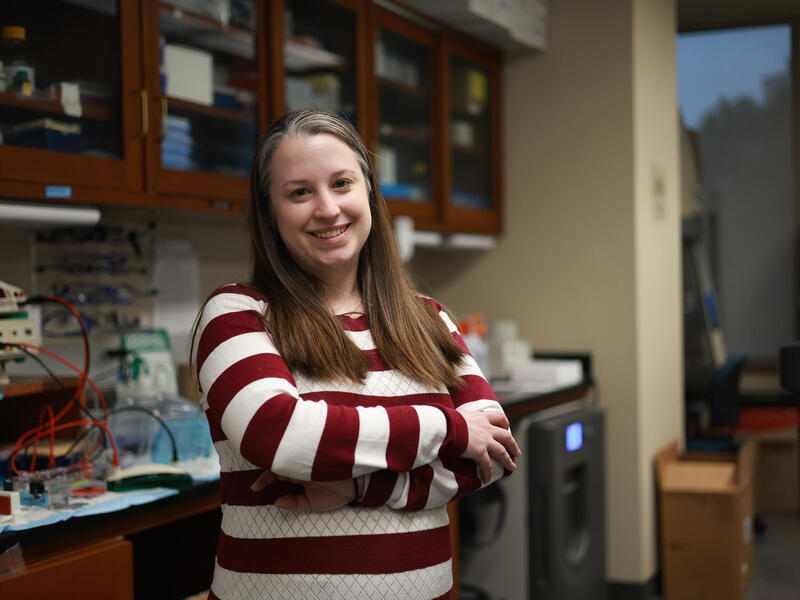

The refined fingerprint will then allow Wijesinghe to develop the detection device using Raman spectroscopy, a technology that measures light frequency. In this case, researchers would use it to detect the pre-eclampsia lipid fingerprint in biological fluids like urine and blood.

Phase two will be a blind prospective study of pregnant women in the regular clinic who are not in the high-risk pool for pre-eclampsia. “We are going to try to tell who is a patient [with pre-eclampsia], and the statisticians will tell us if we are correct or not,” said Chalfant. Results will confirm their ability to accurately predict at-risk patients prior to clinical manifestation of symptoms.

By the end of the study, the team hopes to have developed a noninvasive device that detects pre-eclampsia and possibly other placental disorders before the onset of symptoms. A pregnant woman could be sent home with an affordable and portable machine to test their urine. “They put a drop of urine on it, and it will say either red light or green light,” Chalfant said. “If it’s a red light, you call your doctors and see them immediately. If it’s a green light, you just go on to your next appointment with your OB-GYN as long as you’re not experiencing any other irregular symptoms.”

The device could change the standard of care for obstetrics. Early detection of pre-eclampsia means doctors can begin treating the mother (usually with low-dose aspirin) before it is too late. Chalfant also hopes to find different patterns of placental disorders to learn what causes them. This information could also lead to new treatments.

NIH awarded grants to 18 other research institutions across the United States and Canada to participate in the $46 million initiative that will ultimately improve pregnancy outcomes and long-term health for mothers and babies.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.