Aug. 21, 2018

Northam: Rethinking pain management key to addressing opioid crisis

Share this story

Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam on Monday emphasized the need to treat opioid addiction as a chronic problem.

“This is not something that’s an acute problem. This is not something where you treat someone for their pain and say, ‘Thank you and have a nice day,’” Northam said in a presentation to future health care providers at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine.

“There are changes in the brain. This is a chronic problem.”

That chronic problem has ballooned in recent years into a national emergency. Drug overdoses killed 63,632 Americans in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly two-thirds of those deaths involved a prescription or illicit opioid. Last year, 1,227 Virginia residents died from opioid overdoses, according to the Virginia Department of Health, up from 1,138 deaths in 2016.

Northam, a pediatric neurologist and former Army medic, said the work to address the opioid epidemic involves prevention and treatment and begins with individual patients and their doctors.

“Addiction is a relapsing disorder,” Northam said. “It’s not something that just stops overnight — you just can’t stop someone cold turkey who has been on narcotics. It can be prevented by people like you and me being very careful with how we treat acute and chronic pain. And when prevention does fail, treatment works.”

‘I knew I had a problem but the addiction was overriding my brain’

The event, one of four the governor is participating in at Virginia medical schools this summer, featured a discussion between Northam and Ryan Hall, who is recovering from opioid and heroin addiction.

Hall was a high-achieving student in high school and a three-sport athlete. During his senior year, he broke his leg and tore his ACL, MCL and meniscus during a football game. He was hospitalized and prescribed painkillers, putting him on a multi-year path toward addiction.

Hall quickly went from simply feeling high on pain medication to going through withdrawal when he couldn’t have it. When his prescriptions ran out, he switched to heroin. Hall dropped out of college. He sold his books and his laptop to pay for his dependency. He later was arrested for selling heroin.

“I knew I had a problem but the addiction was overriding my brain,” Hall said Monday. “I knew if I made it past the dope-sickness that I would be all right. But then I would get high again and start the cycle again.”

He has been clean for a little more than a year. Hall’s path to addiction began at a common place, Northam said: a doctor’s office.

“Addiction often starts with a prescription,” Northam said. “It’s a disease, it’s a disorder. And it’s just as common as diabetes and depression, so we need to treat it as such.”

‘We have to treat them’

Northam’s tour comes amid steps taken at state and federal levels to address the opioid crisis.

In 2016, then-Gov. Terry McAuliffe and Virginia Health Commissioner Marissa Levine, M.D., declared the opioid addiction crisis a public health emergency in Virginia. A year later, the White House did the same nationally. In May, Northam signed a bill into law that gives Virginia cities and counties the power to establish local review teams to examine deaths due to or suspected to be caused by an overdose. State police officers now carry Narcan, which can reverse an opioid overdose.

At VCU and VCU Health, efforts are underway to address the opioid crisis through addiction treatment, pain management, health care policy, education and research.

At the School of Dentistry, Omar Abubaker, D.M.D., Ph.D., who lost his son, Adam, to an opioid overdose in 2014, has since introduced lessons on forms of addiction and how to manage patients who have them. Abubaker, professor and chair of oral and maxillofacial surgery, also teaches an oral surgery course to dental students and oral surgery residents in which he incorporates information about pain medications and alternatives to narcotics.

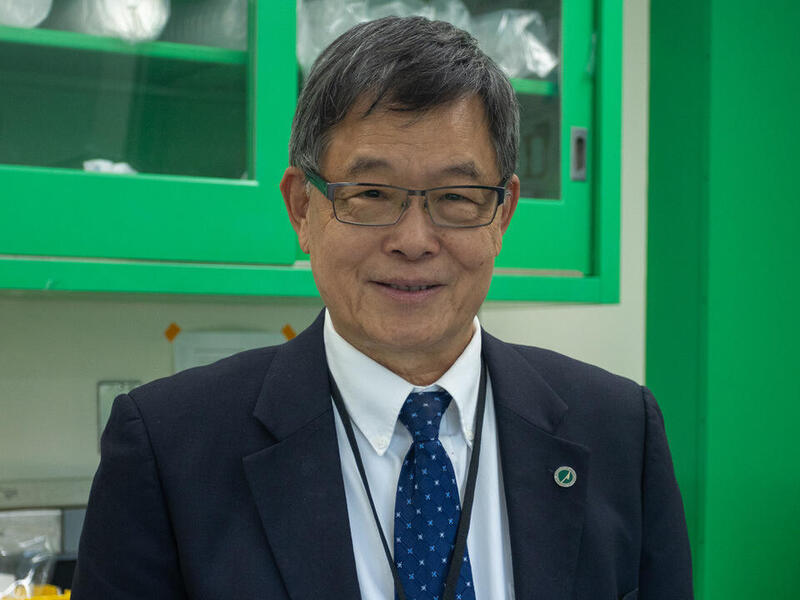

Around the same time Abubaker was introducing these courses, his colleague, F. Gerard Moeller, M.D., a professor in the School of Medicine, was amending curriculum to align with new CDC pain management guidelines. The School of Medicine was the first allopathic medical school in Virginia to adopt the guidelines, which recommend significant restrictions on opioid use in chronic pain treatment and advise physicians to try alternatives to opioids when possible.

“A big part of the opioid epidemic is due to physician practice,” Moeller told VCU News last summer. “Now, we have to do two things: We have to reduce people’s exposure to opioids and, for those who are already addicted, we have to treat them.”

Changing the culture

At VCU, that treatment comes in many forms. This month, the School of Medicine received accreditation from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education for its addiction fellowship, which focuses clinically on addiction medicine and includes emphasis on prevention and pain. Moeller and colleagues also have created hands-on simulations in the classroom. In one, a robotically simulated patient has overdosed on opioids. The students are provided with the patient’s medical history — that of someone who has been in chronic pain treatment with opioids. They are expected to revive the patient with the overdose-reversal drug naloxone.

“We added a more live example of what an overdose might look like,” Moeller said. “We want students to leave with the idea that chronic pain should be managed primarily with non-opioid medications, which has not been the way of thinking in recent history.”

The national reach of the opioid crisis has brought with it “a new change in culture and awareness about opioid overdoses and the opioid crisis,” said Krista Donohoe, Pharm.D., an associate professor in the VCU School of Pharmacy. She and associate professor Laura Morgan, Pharm.D., introduced a new course in 2017 on opioid prescription management and addiction.

The lab course for third-year pharmacy students was created in response to a paper published in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association in which nearly 2-in-5 pharmacists said they were not confident they would recognize when opioids were being illegally resold or given away. Students in the class role-play prescription-monitoring scenarios to better recognize signs of addiction and practice administering naloxone.

“We’re going to continue [the course]. Definitely,” Donohoe said.

Help and hope

Collaboration is key to addressing the opioid crisis, VCU experts said. In 2017, physicians and educators from VCU’s schools of Medicine and Dentistry created a continuing education course that instructs practicing physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants on safe opioid prescribing practices. At the School of Nursing, Abubaker lectures on the opioid epidemic and addiction to psychiatric and mental health nurse practitioner students.

At the state level, Northam said, treatment is a priority. Virginia’s Addiction Recovery Treatment Services program aims to increase the number of outpatient substance abuse treatment providers and improve treatment capacity in the state by enhancing services covered by Medicaid.

It is one of many efforts to address the opioid crisis, Northam said.

“These are providers that are trained to deal with addiction,” he said. “And we have certified substance abuse counselors. We have peer recovery specialists, people like Ryan who can go and share their story with people who are addicted and tell them there is help and hope for them.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.