June 4, 2020

VCU experts create data model to track and predict the spread of COVID-19 across central Virginia

Share this story

In the fight against COVID-19, surviving today’s battles requires social distancing and the best personal protective equipment available. Winning the war requires data — and plenty of it.

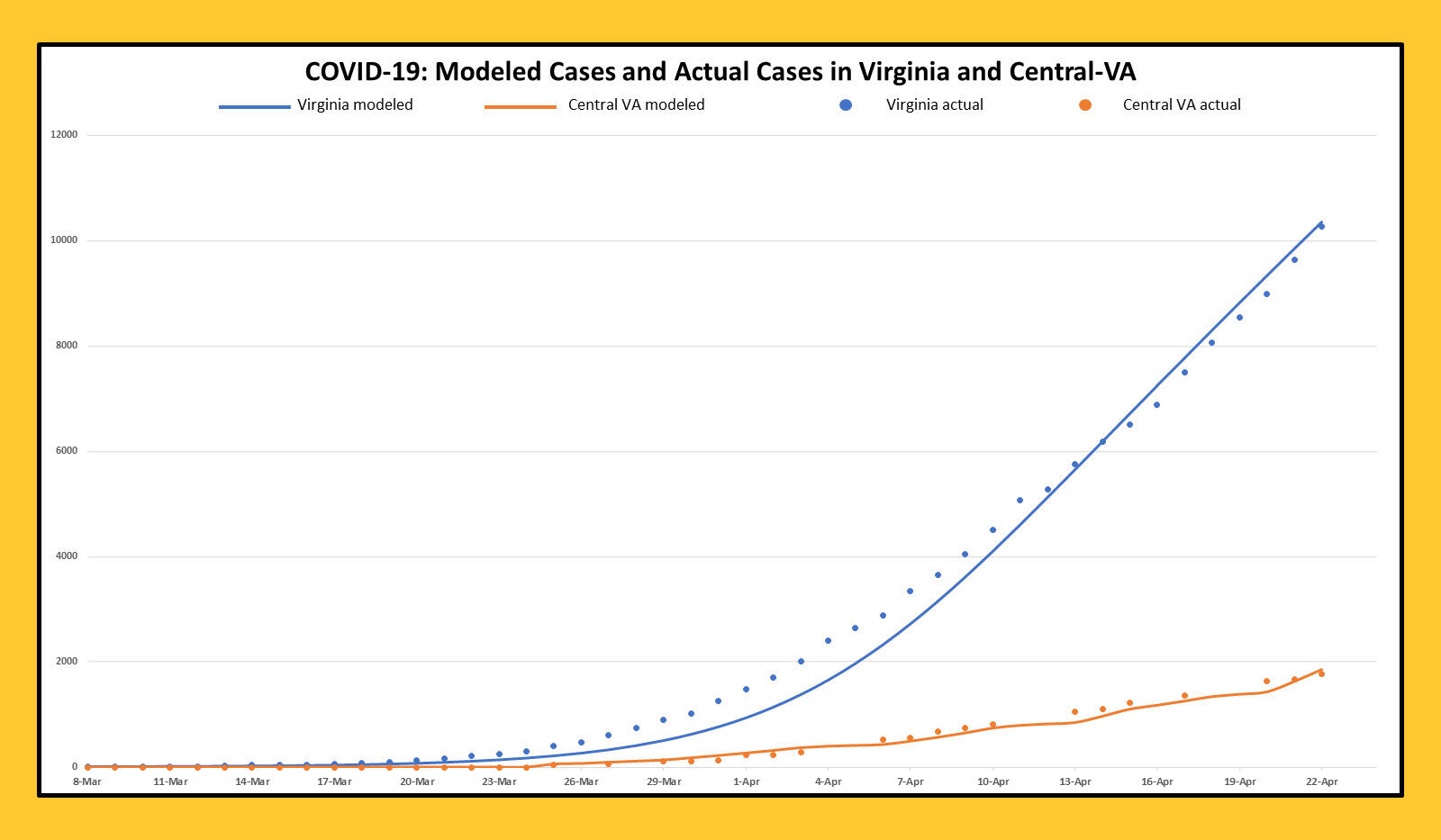

To fortify central Virginia’s arsenal, experts at Virginia Commonwealth University have built a data model to better understand the spread of COVID-19 in the communities most served by the VCU Health System. The model tracks and predicts the impact of the virus across the region bordered by Fredericksburg, the North Carolina border, Hampton Roads and Charlottesville.

“Some of the popular data models that work for multiple states and counties are very generalized and miss out on many of the specific parameters that we need for central Virginia,” said Preetam Ghosh, Ph.D., a professor of computer science in the VCU College of Engineering.

That information includes the number of hospitalizations, length of hospital stays and ventilator use in the VCU Health System, as well as the region’s population density and demographics. VCU’s model includes data back to Virginia’s first reported case of COVID-19 on March 7. It also includes epidemiological models that chart characteristics of the disease, such as the incubation period, transmissibility and its ability to present without symptoms.

“Disease dynamics are typically estimated using existing data and advanced modeling structures,” said Jenna Czarnota, Ph.D., business intelligence analyst for the VCU Health System, adding that the models include disease data from multiple sources.

The data helps the VCU model address questions that guide patient care planning, including equipment allocation and contingency space preparation — as well as more general questions such as whether social distancing is really necessary (an unequivocal “yes”), and whether it’s more effective for interventions to be aggressive in the short term or less aggressive but extended over a longer period.

“Theoretically, we know that aggressive social distancing is 100% effective. If everyone went into their own room for two weeks and didn’t interact with anyone, the virus would disappear, or its distribution would get so small that it would be containable,” said Thomas Yackel, M.D., senior associate dean for clinical affairs in the VCU School of Medicine and president of MCV Physicians.

It doesn’t take a data model to know that’s unlikely to happen, Yackel said, “but if we know the range of those scenarios, we know the boundaries and can make educated guesses about how things might go and how we can be most effective in our planning.”

Because there’s no single instrument that can account for variations in human behavior, the team is comparing trends from its model with results from other models, including those from the universities of Virginia, Washington and Pennsylvania. This creates a model that gives a range of scenarios and outcomes.

“It’s not responsible to make one single projection prediction,” Ghosh said. “This model is very sensitive to the assumptions that you make and the parameters that you feed it. That's why we will always try to produce a best-case, average-case and worst-case scenario.”

So when will the virus peak? A reliable model answers that question in terms of weeks, Ghosh said, not days. The VCU model suggests a peak in central Virginia between mid-May and mid-June based on present conditions and available data. It’s impossible to confirm a peak until after the fact, but Yackel thinks its shape will be fairly certain

“It rises along a concave exponential curve, but after the peak, it will slow down and become convex. If we keep doing what we're doing, it slowly, in a linear way, starts to decrease,” Yackel said.

The purpose of the model is to help VCU’s hospital leadership team make informed decisions as the crisis plays out in the immediate future. “There’s a potential for system overwhelm,” said Amanda Dulin, director of enterprise strategic intelligence for VCU Health System. “So our goal is to optimize operational efficiency and capacity planning for this pandemic so we can continue to provide the highest quality patient care.”

As the team continues to refine VCU’s model throughout the current crisis, it also has its eye on the longer term.

“People have been hoping there was perhaps a seasonality to this pandemic, that it's like the flu: worse in the winter than in the summertime. We don't know that to be true,” Yackel said. “There's a lot of reason to believe that that won't be true, or that the impact will be negligible.”

It is the nature of data models to become more reliable as they acquire more data, Ghosh said, and this makes VCU’s instrument a “durable good” that will be useful in future outbreaks or mutations of the disease.

“We have the data sets right now, and every day, as more data come in, we are better able to calculate infection rates,” Ghosh said. “So the next time this happens, we’re much better equipped to handle a crisis situation.”

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.