Feb. 2, 2026

Medical student’s 3D-printed creations help individuals with disabilities

Share this story

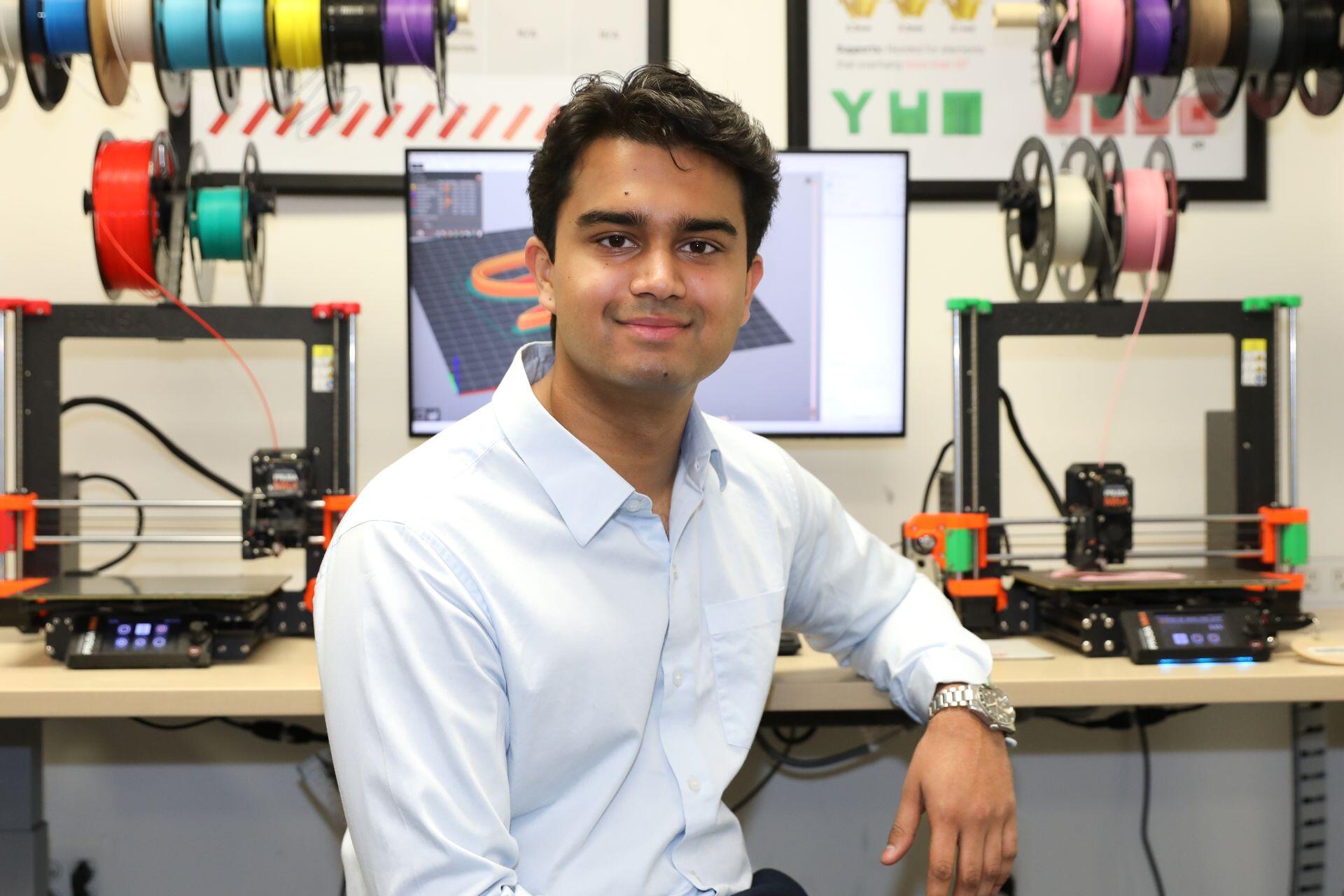

On any given night, you can find Virginia Commonwealth University second-year medical student Nihal Patel in the basement of the James Branch Cabell Library, surrounded by whirring machinery as he scours the details of his latest product design.

Patel, a lifelong tech hobbyist and aspiring orthopaedic surgeon, has designed and manufactured dozens of cost-free 3D-printed assistive devices, from cup holders to pencil grips, to improve the day-to-day lives of individuals with disabilities.

“These tools aren’t changing anyone’s life, but they do, hopefully, make things a little bit easier,” Patel said. “It’s a way for me, as a preclinical student, to get out of the classroom, connect with patients and hopefully improve their situation.”

Navigating new terrain

Technology has lived in the background of Patel’s personal and academic lives for as long as he can remember. Growing up, his information technologist father made it a point to share his profession with Patel and his younger brother. On weekends, the boys would take apart and reassemble an old laptop, absorbing everything he shared along the way about the functions of each part. Even as medicine took the forefront, that early interest remained, and Patel concentrated in data science while earning his bachelor’s degree in biology before attending the VCU School of Medicine.

Patel first thought to combine these interests during a volunteer shift at the Disability and Adaptive Fashion Show hosted by the Friendship Circle of Virginia, a disability advocacy nonprofit. There, he met the mother of one of the models in the show, an elementary school student with quadriplegia, who was frustrated that she couldn’t easily hold a water bottle as she pushed her son’s wheelchair.

“It is such a specific problem that most people wouldn’t ever consider needing a solution for,” Patel said. “But it's the ability to navigate those everyday situations that add up to someone’s quality of life.”

With inspiration and experience in computer-aided design, Patel got to work. He met with the family again to measure the exact dimensions of the wheelchair, and using his hobbyist knowledge, drafted a design for a water bottle holder that could attach to the wheelchair.

Patel then took that design to The Workshop, an equipment depot and makerspace in Cabell, where VCU students can reserve tools like laser cutters, quilting machines and 3D printers. After he fed the design into the 3D printer, the machine slowly deposited a heated filament, layer by layer. A few hours later, he had a small cupholder that would clip onto the boy’s wheelchair.

At the time, Patel assumed it would be a one-off project. But when he watched this child’s mother gush with joy and gratitude, calling family members over FaceTime to show them the device he had just handed her, he was hooked.

“Her reaction is the reason I’m still doing this,” Patel said. “She had been through so much and I think she just felt very seen. I want to make others feel that way and that experience showed me a way of doing it.”

From ideas to innovation

For Patel, the manufacturing process doesn’t begin with measuring dimensions or sketching out an idea. The first and more important step, he said, is connecting with patients and their families to understand what they would want from an assistive device.

Patel meets many patients while shadowing physicians across the VCU Health system, observing appointments with an eye for opportunities to offer his skills. He has created some devices, such as a screw-top bottle opener he recently printed, using free designs in the assistive devices library of Makers Making Change, a Canadian nonprofit that hosts a crowdsourced public database of more than 200 3D-printable models. Other cases require Patel to spend weeks designing, troubleshooting and testing to create a product that suits a patient’s specific needs.

The process can be taxing, Patel said, and creating a successful device from scratch involves multiple rounds of trial and error. His most recent project is a custom cane holder for a pediatric patient with limited dexterity in his hands. The device can be mounted on the patient’s wheelchair or a table, and Patel has spent hours meticulously tweaking the most minor of details, down to altering the width of threads in a screw attachment to be more accommodating for someone with limited grip strength.

“It can be frustrating, especially when I think I finally figured it out and something fails,” Patel said. “But the look on a patient’s face when they get the final product is so worth it.”

Building bridges

In addition to connecting with community members, Patel’s 3D printing projects have led him to collaborators across VCU. With no formal training in design or engineering, he regularly reaches out to undergraduate students in the College of Engineering for design advice and troubleshooting.

Patel’s interest in assistive technology has also caught the eye of faculty mentors in the School of Medicine, including James Engels, M.D., an associate professor in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and division chief of pediatric orthopaedic surgery at the Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU. Engels connected with Patel last year, and said he was impressed with the then-M1’s “enthusiasm for ideas and creativity” when he pitched the idea to use 3D printing to create no-cost assistive devices.

Along with that creativity is a humble thoughtfulness, which drives Patel in identifying ways he can quietly help others. Engels, who regularly interacts with young patients with disabilities, commended Patel’s instincts and ingenuity as a problem-solver and future physician.

“The devices he has developed are simple but quite impactful, and they enable a greater level of independence for these children,” Engels said. “Nihal has a talent for identifying ways to make life easier for them.”

As he considers other new ways technology can be used to assist patients, Patel said he appreciates the freedom to pursue personal interests that the School of Medicine, and VCU at large, has allowed him.

“There is such a wealth of knowledge at VCU, and everyone has been so open and interested in helping me where they can,” Patel said. “I wouldn’t be able to do any of this without the resources here, both machine and human.”

This story was originally published on the School of Medicine website.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.