Dec. 5, 2017

For children with ADHD, a brief, school-based program can help dramatically with homework problems, study finds

Share this story

Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder who took part in a brief, school-based program displayed significant improvements in their homework, organization and planning skills, according to a new study led by a Virginia Commonwealth University professor.

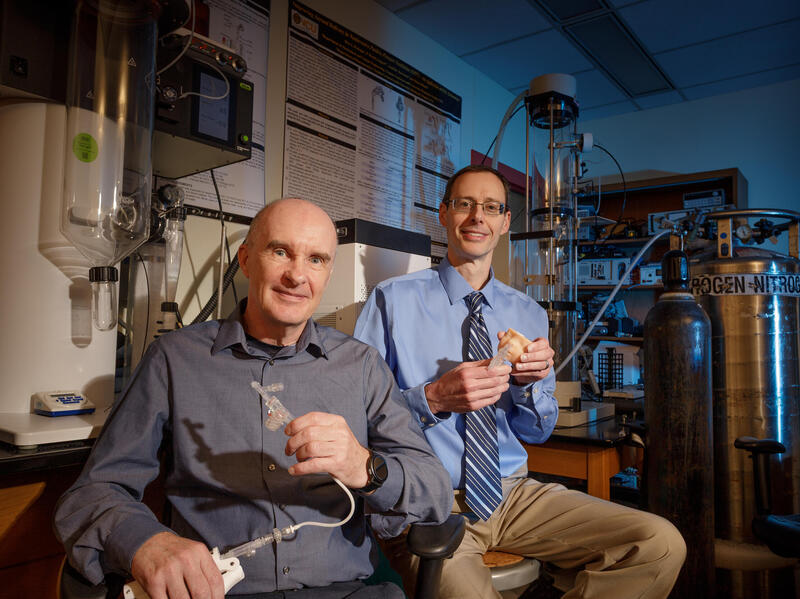

The study, “Overcoming the research-to-practice gap: A randomized trial with two brief homework and organization interventions for students with ADHD as implemented by school mental health providers,” will be published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology and was led by Joshua Langberg, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Psychology in the College of Humanities and Sciences.

The study tested the effectiveness of the Homework, Organization, and Planning Skills intervention, better known as HOPS, which has been implemented in hundreds of schools across the country. Langberg designed the HOPS program to help children with ADHD improve their organization, time management and planning skills related to homework completion.

For comparison, Langberg designed a new intervention called Completing Homework by Improving Efficiency and Focus, also known as CHIEF, which focuses on addressing the more behavioral aspects of homework completion for children with ADHD. In CHIEF, school counselors carefully manage student behavior, set homework completion goals and support them in completing assignments and studying for tests.

Both programs were implemented during the school day in Chesterfield County middle schools. Each student in the study participated in 16 meetings with a school counselor, with each meeting taking 20 minutes or less. The participants, 280 middle school students with ADHD, were pulled from elective classes, and school counselors who graduated from VCU implemented the interventions.

“This was an attempt to evaluate an intervention under real-world conditions,” Langberg said. “Most research-developed interventions never get used in school and community settings because they are too costly, require lots of training and supervision, and are complex. We set out to design and evaluate ADHD interventions that are brief and feasible to implement under real-world conditions with typically trained providers.”

Students with ADHD in both HOPS and CHIEF displayed significant improvements in homework problems according to their parents, the study found. The students who participated in HOPS also made significant improvements in organization and planning skills according to both their parents and teachers.

While both interventions were effective, the study found, HOPS was clearly more helpful with the most severe cases, such as students who had more behavioral challenges at home and in the classroom.

ADHD is one of the most prevalent childhood mental health disorders and is associated with significant academic problems, including low and falling grades and high rates of dropping out of school.

Academic impairment in children with ADHD is often the result of problems managing and completing homework, with students often failing to record assignments, losing material, procrastinating and having difficulty completely the work efficiently. Overall, research has shown, students with ADHD turn in approximately 15 percent to 25 percent fewer homework assignments each semester compared with their peers.

“If you talk to parents [of children with ADHD], they’ll often say, ‘My child gets A’s and B’s on tests, but he turns in 50 percent of his homework, so he has a C or a D in the class.’ That’s a common thing,” Langberg said. “So in that case, you would essentially be saying that struggles with homework are preventing that student from demonstrating their full academic potential.”

Improving homework skills is especially important for children with ADHD because homework problems have been shown to be highly predictive of future academic success.

Langberg collaborated on a previous study that followed close to 600 students with ADHD from elementary school through college and found that parents’ ratings of their child’s homework problems in elementary school predicted their GPA in high school to a greater degree than their intelligence, achievement scores, ADHD symptoms and medication use.

These are skills just like math or reading skills and need to be taught, shaped and evaluated over time.

“Teachers and schools sometimes assume that as students get older, they will automatically learn how to organize their materials, plan ahead and work efficiently. It doesn’t work that way for many students, including students with ADHD,” Langberg said. “These are skills just like math or reading skills and need to be taught, shaped and evaluated over time, just like we do for traditional academic skills.”

With this new study, Langberg shows that schools can teach these skills and that it can be done in a relatively brief and feasible manner. Langberg hopes that developing briefer and less costly interventions will help overcome the research-to-practice gap.

The project was funded by a $2.4 million grant from the Institute of Education Sciences in the U.S. Department of Education. The grant paid to hire six school counselors to implement the interventions in seven middle schools at no cost to the district. Five of the six school counselors stayed on and now work in Chesterfield County Public Schools full time. Additionally, as part of the grant, all 280 students and their families received a comprehensive mental health evaluation and assessment report prior to receiving the intervention.

“Overall, this project highlights the benefits of community-based research and supports VCU’s focus on research in that area,” Langberg said.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.