Oct. 30, 2012

A Crime Scene Education

Share this story

A gruesome crime scene is no place for a child. Yet dozens of parents recently brought their children to a place strewn with the evidence of criminal activity, such as broken glass and splattered blood.

Thankfully, the crime scene was staged as part of a workshop for middle school children sponsored by the VCU College of Humanities and Sciences' Department of Forensic Science and the Library of Virginia for the annual Virginia Literary Festival. About 25 Forensic Science students volunteered to help with the staging of various crime-scene stations.

But what does a crime scene have to do with literature? Ask Marcia Talley. The mystery novelist grew up devouring mysteries featuring Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys and has been a fan of television crime procedurals for years. Talley led the writing portion of the workshop. While Talley has led workshops for middle schoolers before, this is the first time the participants had actual hands-on experience with crime scenes and forensics beforehand.

In the past, "I would have to provide hints and clues, but here, they … have actual physical stuff," Talley said. "They're … honing their observation skills, too, which is very important for a writer. You see it, and you internalize it, and you never know when it's going to come out in a story."

As the students arrived one by one, they were ushered into an observation station where they practiced using their senses to identify objects hidden in a bag.

"We hope it's a pretty unique learning experience for them," said Michelle Peace, Ph.D., interim chair of the Department of Forensic Science. "We're excited about this opportunity to join up with Marcia Talley. … She's really interested in talking to young people about how to write mysteries and what better way to get them to think about those mysteries when they actually have some kind of experience to also think about?"

Besides getting children interested in writing, the workshop served the purpose of getting children excited about science as well.

"This is such a cool way to get this age interested in science, because it turns out studies have shown that in middle school that's when they begin making those life-determining decisions," said Marilyn Miller, Ph.D., associate professor in forensic science. "And we want to hook them into science early."

After everyone had arrived, the junior crime scene investigators headed toward the lab where they alternated between six stations, each focusing on a different component of forensic science.

"Each exercise is meant to introduce concepts to them," Peace said. "And those concepts are … about the power of observation. The importance of documentation and sketching. How to classify and identify things. There's going to be a fingerprint exercise. There's going to be a hair exercise."

Other exercises dealt with a variety of trace evidence such as soil, hair and paint chips. Miller's station focused on blood splatters.

"We're going to show them some special ways in which physical evidence can help put together and solve a crime based on what we find at the crime scene," said Miller, who used watered down paint instead of the pig blood normally used in her classes. "Blood falls from different heights and depending upon the size of the resulting stain, you can figure out the height from which the blood fell. So is somebody bleeding from close to the ground or are they standing up? Or are they in the process of standing up or are they in the process of falling down?"

At the sketching/documentation table, students were first tasked with creating a permanent record of a scene in relation to its evidence. They then switched "scenes" and had to re-create a scene based on their peers' documentation.

The final station dealt with a classic piece of physical evidence: fingerprints.

Graduate students Mikaela Romanelli and Stephen Raso explained different identification characteristics — such as bifurcations, ridge endings and islands — and classification patterns.

"When you're talking about classification, you have three different types: your loops, whirls and arches," said Romanelli. "So then when you want to try to ID someone, you need something that's specific to that person. Bifurcation is when it splits. Then you have ending ridges which is when your ridge just stops."

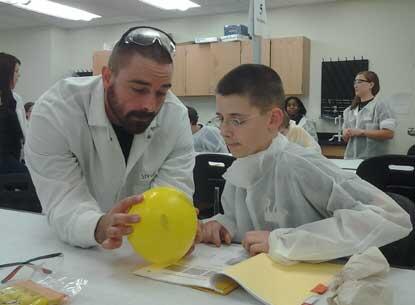

The investigators then made a thumb print on a deflated balloon. Once inflated, they had a large print to study.

"When you combine all the different ones that they have on that entire fingerprint, that's where you can get the uniqueness," Raso said. "Me and you might both have a bifurcation right there, but somewhere else, there's going to be something different. So it's not the one specific thing that you're looking for, it's the entire picture, that combination of uniqueness that you're going to get."

Once done with the lab exercises, the children had one last chance to test their observational skills before applying their newfound knowledge in Talley's mystery-writing workshop. As they made their way down the hall, a surprise mock crime scene — replete with a body and the telltale signs of a struggle — awaited them.

Talley used the encounter to talk to them about what they experienced and how to translate that into the written word, Peace said.

"It's our mission with these exercises not to necessarily make sure that they walk away completely understanding the science behind these things, but that the young people walk away with some inspiration about the concepts," Peace said.

Subscribe to the weekly VCU News email newsletter at http://newsletter.news.vcu.edu/ and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox every Thursday.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.