Sept. 15, 2006

How the Eye Works

Share this story

Virginia Commonwealth University researchers have been combining tools from biochemistry, electrophysiology and genetics to explore the biology of the eye.

Understanding the differences between retinal rod and cone photoreceptor cells will help scientists in their pursuit to develop methods to diagnose, treat and prevent diseases of the eye such as retinitis pigmentosa and macular degeneration.

Advancing research in this field is Ching-Kang Jason Chen, Ph.D., an associate professor in the VCU Department of Biochemistry, together with researchers from VCU and other U.S. laboratories, who have been examining the molecular details of the visual signaling pathway and the mechanisms underlying the death of retinal photoreceptors.

Last month, in the journal Neuron, the team reported the kinetic differences between light-sensing cells known as rods and cones in the mouse retina. According to Chen, the work has important implications in a ubiquitous cellular signaling mechanism involving a class of proteins known as the G-proteins, and their cell surface receptors known as GPCRs.

The team discovered that the shut-off of a particular G-protein, known as tranducin, determines the duration of the response to light in rod photoreceptors. Scientists had initially believed that the lifetime of activated GPCR known as rhodopsin was responsible for this response. Chen said that by accelerating the deactivation of the G-protein in the rod cells, the overall rate of responses are transformed to mimic those of the cone cells, which are less sensitive, but transduce light at a faster rate.

Diseases of the eye, such as retinitis pigmentosa and macular degeneration, involve the chronic loss of retinal photoreceptors.

"Retinitis pigmentosa and macular degeneration are increasingly becoming more of a health concern that affects the nation as the population ages. Understanding the basic science and mechanics of the eye will help researchers develop potential treatment options that do not currently exist," Chen said.

As early as the 1940s, scientists were studying the biochemical reactions in retinal photoreceptors in which light energy is transduced into neuronal signals through a process called phototransduction. This occurs through a signaling mechanism that involves G-proteins and GPCRs. In the United States, approximately 40 percent of the pharmaceuticals sold target GPCRs.

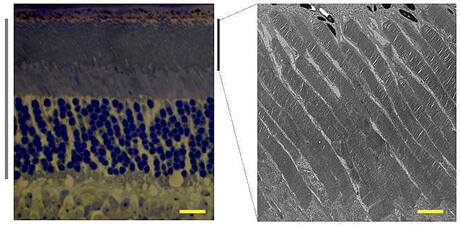

Rod cells are sensitive to light and are responsible for helping to see in the dark or in dimly lit settings. In contrast, cone cells allow the eye to recognize color and fine visual detail. Cone cells are found primarily at the center of the retina, in the region known as the macula. Chen said that rods and cones together enable the retina to respond to a dynamic range of light stimuli, ranging from high noon to starlight.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Chen collaborated with researchers from VCU; the Center for Neuroscience, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of California; the Howe Laboratory of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary; and the Department of Biochemistry and Department of Ophthalmology at the Baylor College of Medicine.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.