Jan. 23, 2025

VCU author investigates U.S.-Mexico migration in the early 20th century – and its enduring legacy

Share this story

Migration between Mexico and the United States is the largest emigration of people between two states in modern history. Some of that history has been well-explored, such as the Bracero Program – it brought more than 4 million Mexican citizens to the U.S. from 1942 to 1964 to provide agricultural labor – as well as recent migration. But little is known about how mass migration arose in the first half of the 20th century.

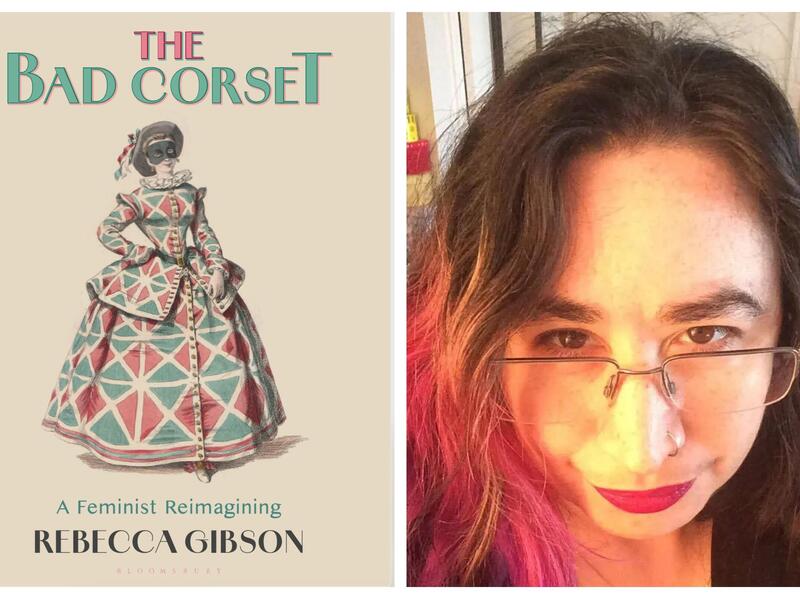

In his new book, “Between Here and There: Creating the Political Economy of Mexican Migration, 1900-1942,” Virginia Commonwealth University researcher Daniel Morales examines the creation of transnational migratory networks across Mexico and the United States in the 20th century, illustrating how large-scale migration became entrenched in both countries’ socioeconomic fabric.

“Once underway, mass migration began to change both Mexican and American society,” said Morales, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of History in VCU’s College of Humanities and Sciences.

In “Between Here and There,” Morales investigates the creation of modern U.S.-Mexico migration patterns. He spoke to VCU News about his discoveries and their enduring dynamics.

What is some helpful initial context about Mexico in the early 20th century?

There was never a time when Mexico’s economy was strong enough to dissuade people from leaving for El Norte. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Mexican elite saw Mexico as the rightful place for all Mexicans; they viewed migration as desertion and sought the return of migrants.

The Bracero Program, once underway, created its own dynamics, driving more people – both documented and undocumented – across the border. Officials increasingly saw migration as economically and politically necessary, a political safety valve, and used it to bolster their state-building project.

The program formalized and provided state sanction for the political economy of migrant labor between the two countries while drawing a distinction between “legal” migration (that is, migration organized by the Bracero Program) and “illegal” or undocumented and unsanctioned labor migration.

And your research goes back even further.

This book revisits the era of the first mass migration – between 1910 and 1940, from the Mexican Revolution to World War II – and reconsiders the formation of the Mexican-American community within the broader context of ongoing circular migration, both between the U.S. and Mexico and within the U.S.

The latter dynamic has been least recognized or understood. Migrant workers trekked around the country following work in agriculture, mining and industry. They organized mutual aid organizations and unions. And they sought to return to their hometowns in Mexico. So, circular migration and settlement were not successive phases, but always concurrent and dynamically related. This can be best seen by going full circle – starting and ending with communities in Mexico.

While cyclical migration patterns and Mexican villages’ dependence on remittances in the late 20th century have been widely examined, this model was established decades earlier.

A century later, how can we envision the legacy of this migration?

Through an analysis of the interplay between the U.S. and Mexican governments, civic organizations and migrants on both sides of the border, “Between Here and There” offers a revisionist and comprehensive view of Mexican migration as a socioeconomic system – one that reached from the Texas borderlands to California, as well as to Midwestern farming and industrial areas. It illustrates how large-scale migration became entrenched in the socioeconomic fabric of both nations, drawing on the largest cohort study of Mexican migration during these decades.

Reacting to the political and economic events of the first half of the 20th century, migrant workers become increasingly assertive, even as migration becomes a major political issue in both societies. Those in Mexico claimed an expansive form of citizenship and land, while those in the United States joined efforts to claim New Deal rights, creating a base for later organizing. These dynamics shaped the establishment of the Bracero Program and shaped migration patterns that continue through the present day.

What are other key takeaways from “Between Here and There”?

A transnational and borderland perspective – rather than local or frontier – highlights the connections that allowed people to not only survive but organize. Through their actions, Mexicans created an infrastructure of brokers and associational networks that sustained their communities and guided them as they made their way through both countries.

Once underway, mass migration began to change both Mexican and American society. As people left and others came back, the resulting information and capital changed conditions on the ground and created pathways for others to follow. This new economy made it easier to move but also tied many families and towns into continuous patterns of migration in order to maintain economic stability. Migration evolved from something that a few men did to something in which many participated; even those left behind were active participants.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.