June 22, 2021

How one center’s work gave a voice to thousands of primary care providers during the pandemic

Share this story

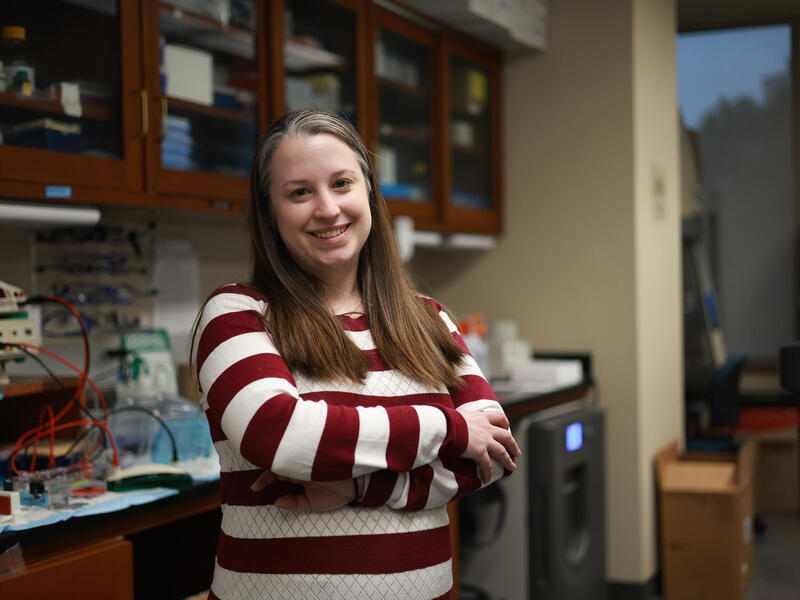

When Rebecca Etz, Ph.D., and her team at the Larry A. Green Center surveyed doctors around the country about the challenges they were facing during the COVID-19 pandemic, they received stories of desperation and stress that were alarming.

“There were a lot of ‘wow’ moments,” said Etz, co-director of the Green Center and a professor in the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine’s Department of Family Medicine and Population Health.

“Primary care is not an industry that carries a large reserve, so many of them fell into trouble very quickly, and there was no funding relief for primary care. There was no pandemic plan that involved primary care,” Etz said.

Solving the problems that face primary care as a field is key to the mission of the Larry A. Green Center, a collaborative center based at VCU in partnership with faculty at Case Western Reserve University and the University of Colorado, as well as individuals from across the industry. The center, founded in 2017, focuses on advancing primary health care for the public good. Their team’s work during the pandemic emphasized the value of being a voice for primary care providers everywhere.

Etz and her team kicked off the COVID-19 survey on March 13, 2020, when President Donald Trump announced that the pandemic was a national public health emergency. The group discussed the fact that there is no national database of information about primary care practices — data such as the prevalence of COVID-19 in practices, the number of patients seen, the cost of the transition to telehealth, the number of practices changing their hours, access to funding or personal protective equipment.

“We immediately all looked at each other and realized, ‘this is going to be rough for primary care,’” said Sarah Reves, deputy director of the Green Center and a nurse researcher for the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health.

Etz said the survey was so important because there is no national coordination of primary care.

“There is no national anything, and primary care was about to be hit by this pandemic. We needed the ability to understand what was going to be happening or who needed help,” Etz said. “And so we decided we should get something going right away.”

Etz’s group decided the weekly surveys had to take less than three minutes to complete and questions needed to be things that the team at the Green Center could act on within the next week, putting the data to use to help make the work of the primary care physicians visible and get support for their needs. The idea was not to have the doctors use their time to send data only for the sake of doing research. Etz vowed to only collect information that could be used and publicized to be immediately helpful to doctors and relevant to their day-to-day struggle.

“That was probably 10 a.m. on Friday, March 13, and by 6 p.m. data manager and analyst Martha Gonzalez was sending the first survey out to 20,000 clinicians,” Reves said. “We figured if we received 30 responses, we'd be happy. And we had 535 by Monday morning.”

Emotional and impactful responses

To date, 28 surveys have been sent out to tens of thousands of providers, asking questions such as how the pandemic has affected clinicians’ stress levels, burnout, staffing, ability to stay open, pay for their work, the health burden that their patients carry and what kinds of inequities they've seen among their patient populations.

With a team of four full-time and over a dozen contract staffers working on the surveys, the hours were long but the results were rewarding.

“You're getting comments from the clinicians who are filling these out saying: ‘Thank you so much. I look forward to these once a week and it makes me feel like I'm being heard by someone. Every time I get the survey, I fill it out and then I cry because nobody asked me how I am, except for you guys,’” Reves said.

It was difficult for Etz to keep watching and documenting doctors’ burnout and bleak financial outlook while decision-makers were not responding.

“These are people who go into a profession because they feel the altruistic interest in protecting the health of the population,” Etz said. “That's the motivation. They're not in it to just to earn. And now they're saying, ‘don't make me pay for the care that I deliver. At least make it possible for me to take care of these people who have no one else on whom they can rely.’”

The surveys revealed some harrowing facts.

“Family medicine doctors died of COVID at a rate five times that of any other specialty. That's the price we pay when we [nationally] don't provide them with any protective gear,” Etz said. “We saw incredible mental health strain among practices. We saw them being paid for less than half of their work. Being asked to take on new billing codes that were extremely complicated to use. They would turn in telehealth billing, and they would get denied and have to turn it in again at remarkably reduced rates.”

The surveys’ summaries were able to quantify stories of the huge financial strain of COVID-19 on primary care physicians.

“We have many practices in which clinicians took out second mortgages and personal loans because they could not get provider relief funds,” Etz said. “The complicated process and requirements for accessing funding made available through the CARES Act made it unlikely that anyone other than large systems would be able to access relief. It went to restaurants, it went to emergency rooms – places that needed it, but so did those protecting the health of the nation.”

Etz points out the irony that primary care in 2019 saw 99.8% of all respiratory illness in the U.S., and with a pandemic that was based on respiratory illness, the government gave primary care very little funding. Even while practices were going bankrupt, the surveys showed doctors continuing to help patients.

The day after George Floyd was killed, Etz’s team surveyed doctors about the impact of racism in the practice and on health and whether racism was a public health issue.

“For that survey, 85% of the respondents said that racism was a public health issue,” Etz said. “We saw clinicians saying 10% to 12% of patient visits they were getting at that time appeared to be people who had experienced an actual physical impact of racism and another 30% to 40% had psychological or emotional impacts of racism.”

Clinicians also said that primary care should have been involved in distributions of vaccines as a traditional venue for inoculations.

We figured if we received 30 responses, we'd be happy. And we had 535 by Monday morning.

At the big table

Doing the surveys felt timely and crucial and catapulted Etz, her team and the issue of primary care support to new heights and provided a platform she and her staff never thought they would be able to use, such as writing letters to members of Congress.

“We ask people in the survey, if you could say anything to Congress, what would you like to say? We were compiling them, and I'm sitting and thinking, ‘This is not a letter I ever thought I'd be writing,’” Reves said.

Etz and Reves found themselves having meetings with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and international medical associations that wanted to see the results of the COVID-19 surveys to inform decision-makers and form policy on the pandemic as it lingers on.

Now the team frequently sends summaries of the doctors’ voices from the COVID-19 surveys to the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives minority and majority leaders, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“[Etz] is the most unassuming person and very often feels like she's the little kid who got bumped up to the adult table at Thanksgiving and was asked to carve the turkey all at the same time,” Reves said. “It has been a ridiculous year. The number of requests and level of interest shows how little other data there are.”

Nonstop work to capture doctors’ dire conditions resulted in regular calls from U.S. Congresswoman and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi's office, the U.S. Joint Economic Committee and the Federal Telemedicine Working Group — a group of federal leaders focused on telehealth that includes such agencies as the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NASA.

“We became the people who had data and, when you have data, it means everything,” Etz said. “It was a bizarre feeling. I'm still trying to get used to it. We have had a lot of those ‘wow’ moments. Not just sending our data to the [President Joe] Biden transition team, but then getting feedback from them and hearing they want more. That was like, ‘Oh my God, they're actually listening.’”

Extraordinary recognition

In December, Etz won the Primary Care Collaborative’s Barbara Starfield Award, which recognizes excellence in primary care leadership. And in May, Etz received the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Advocate of the Year Award as a primary care advocate.

“My team has been truly extraordinary,” Etz said. “They have worked an unbelievable amount. I don't think anybody will ever realize how much they've worked, nor the kind of toll it takes to read all the sadness of the people who are responding [to the surveys]. It's a real hit each time we do it. It's a privilege.”

But Etz still sees herself as “this anthropologist, leading a small can-do team from my dining room table and everybody doing what they can working from home during the pandemic.”

“To get that kind of recognition for the work we're doing was just extraordinary, humbling really,” Etz said.

Receiving the awards gives her team added recognition, she said, making them a known entity to organizations that hadn't heard of the Larry A. Green Center before.

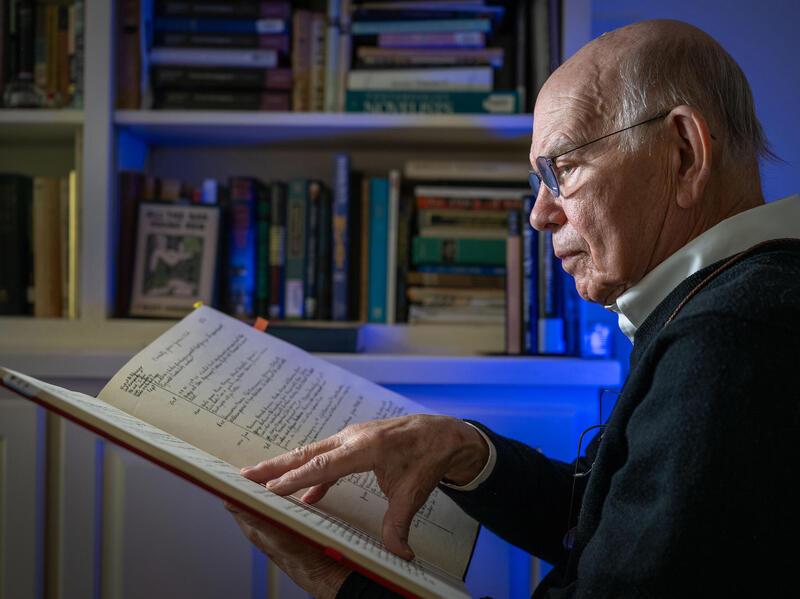

Green Center co-director Kurt Stange, M.D., Ph.D., based at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, has known Etz since she was a postdoctoral researcher at Rutgers’ Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

“She's a unique resource for doing good in the world. She's fairly selfless in how she approaches things and is really trying to give voice to the role of the generalist and health care as a force for integration in a very fragmented system,” Stange said.

National impact and more funding

With extensive media coverage, the COVID-19 surveys highlighted how the payment system for primary care being based on services delivered creates a lack of funding for infrastructure.

A 400-page consensus report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine titled “Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care” used findings from the Green Center’s surveys to help highlight numerous weaknesses. The report includes the perils of fee-for-service funding for health care; the opportunities for better inclusion of primary care in national pandemic planning and in congressional COVID-19 relief bills; the evolution of payment models surrounding telehealth; and the profound effect that social drivers of health have on the probability that a person will live or die. Etz and Alex H. Krist, M.D., a professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health and immediate past chair of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, were among the report’s co-authors.

Survey results have been used by many other organizations to effect change. Beth Bortz, president and CEO of the Virginia Center for Health Innovation, was able to use the survey data to advocate for the establishment of the Governor’s Task Force on Primary Care. Using the Green Center’s data, and collecting some of their own, that task force was able to deliver 750,000 units of protective equipment to practices in Virginia free of charge.

“I think the biggest moments may well be people who just simply say, thank you,” Etz said. “We get a lot of emails from people who are taking the survey who thank us for noticing them, for giving voice to what they're going through, for continuing to be an outlet for them during a very difficult time and for advocating on their behalf.”

She thinks primary care is experiencing a moment right now because many people are understanding that this is a critical resource and it's been neglected for some time.

“I see this as putting a spotlight on the work that primary care does more than us, which is really cool because we can use that to continue to advocate on behalf of those people who take care of all of us,” Etz said.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.