Feb. 12, 2026

Northern Virginia data center air pollution rivals power plant emissions, VCU research finds

Share this story

Northern Virginia has the highest concentration of data centers in the world, and residents and environmentalists throughout the state have criticized the land use impacts and energy usage of the massive server farms. But the backup generators that occasionally power those data centers also threaten local air quality, according to new Virginia Commonwealth University research, and in some cases even exceed emissions from nearby power plants.

Data centers are generally equipped with diesel-powered backup generators, which can power the entire facility in the event of planned and unplanned power outages. When running, the generators release air pollutants that are harmful to human health, including carbon monoxide, nitrous oxides and particulate matter.

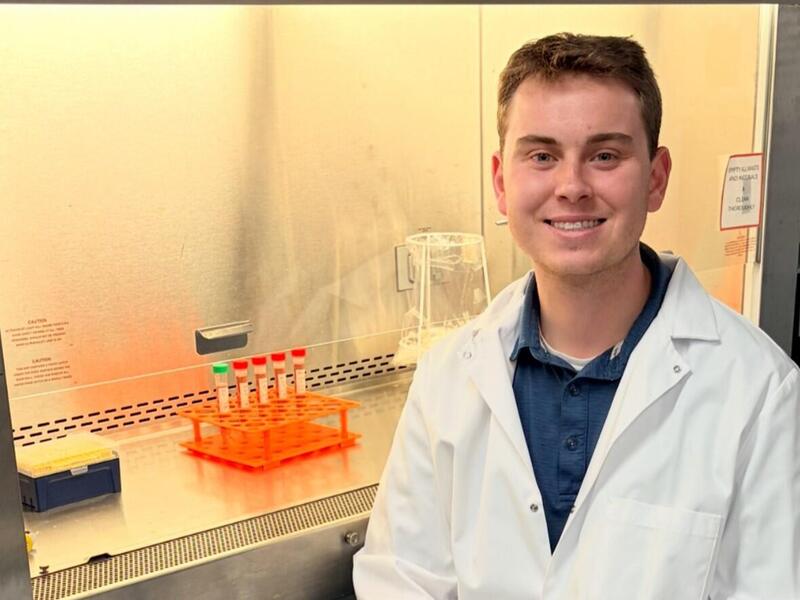

“Something that we were surprised to learn through this process is you’d rather be living next to a natural gas power plant than living next to a whole bunch of data centers, in terms of the total amount of air pollution they put out per year,” said Damian Pitt, Ph.D., an associate professor in VCU’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, who conducted the study alongside colleague I-Shian (Ivan) Suen, Ph.D., and graduate student Ellie Plisko.

Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality issues air pollution permits for each data center with backup generators. In this study, the researchers spatially mapped air pollution from 138 Northern Virginia data centers located in Arlington, Fairfax, Loudon and Prince William counties, as well as five independent cities within those counties, using the agency’s measurements of both permitted and actual air pollution.

The team found that emissions from data centers’ generators increased substantially in the region between 2015 and 2023: Carbon monoxide emissions increased by 196%, nitrous oxide emissions rose by 111%, and dangerous particulate matter emissions jumped by 139%.

Currently, those data center emissions in Northern Virginia make up 3% of carbon monoxide, 11% of nitrous oxide and 3% of particulate matter pollution from the region’s point sources, which include stationary facilities like power plants.

However, those numbers only make up around 4% to 7% of the total tons per year of emissions that the region’s data centers are permitted to release. If they reached their maximum allowable emissions, data centers would make up 33% of the region’s total nitrous oxide emissions and 49%, 74% and 50% of point source emissions for carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide and particulate matter pollution, respectively.

“When you look at the total emissions under the permits, this kind of worst-case scenario, it’s just leagues beyond anything that is associated with any other existing facilities in the region,” Pitt said.

And while most data centers run their backup generators infrequently – about 5% of the time, including scheduled test runs – some facilities are already releasing 30% or more of their permitted emissions. If meeting their permitted limits, data centers in the region could emit 10 to 20 times more pollution than they do currently.

That’s not an impossible scenario, the researchers said: In January, the U.S. Department of Energy allowed a regional grid operator to ask data centers to run their generators in order to provide additional power to the grid during winter storm Fern, and future similar events could push data centers toward the upper limits of their pollution permits.

Additionally, some clusters of data centers are emitting pollutants at levels that exceed emissions from facilities like Dominion’s Possum Point Power Station. Those clusters mean that some neighborhoods and counties are more affected than others: For instance, while densely populated Arlington County does not contain any data centers, Prince William and Loudon counties contain the 10 most affected neighborhoods.

To find out whether pollutants from data center generators are unevenly affecting different demographics, the researchers overlayed regional census maps on top of their air pollution maps. Areas with lower household incomes, lower education levels and higher proportions of renters to homeowners tended to be polluted with higher levels of carbon monoxide and nitrous oxide pollution from data centers.

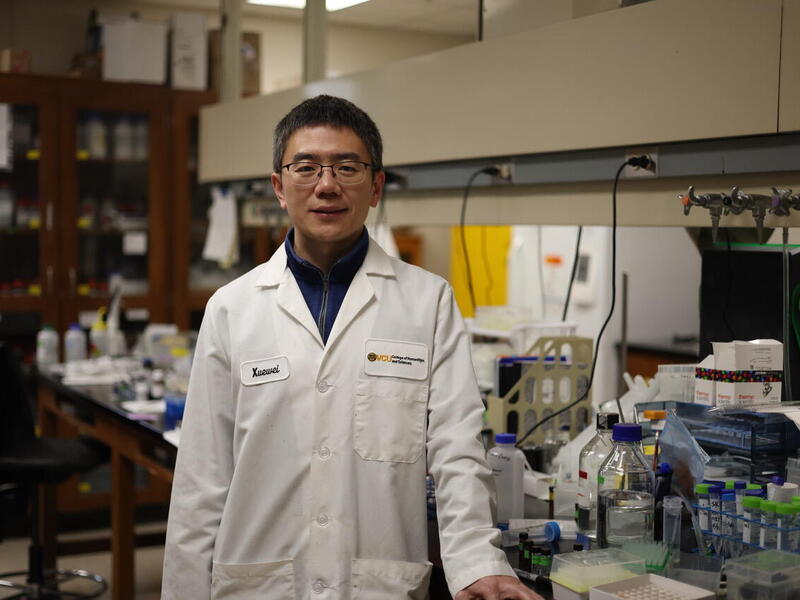

“The big picture here is basically that places that have high emission levels or exposure are correlated with less advantaged or vulnerable populations overall,” Suen said.

The researchers also noted that while data center emissions in Northern Virginia are currently dwarfed by those from cars, trucks and other motor vehicles, they are an increasingly significant source of pollution.

“Our takeaway is that there is already a concerning amount of emissions, just based on what’s going on now,” Pitt said. “But were it to approach anywhere near those permitted amounts, it would be a whole different ballgame."

Each issue of the VCU News newsletter includes a roundup of top headlines from the university’s central news source. The newsletter is distributed on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. To subscribe, visit newsletter.vcu.edu/. All VCU and VCU Health email account holders are automatically subscribed to the newsletter.

Subscribe to VCU News

Subscribe to VCU News at newsletter.vcu.edu and receive a selection of stories, videos, photos, news clips and event listings in your inbox.